Head and neck surgeries pose significant airway management challenges due to anatomical distortions, tumor masses, prior radiation, and surgical scarring. The anesthesiologist’s role in these procedures extends far beyond induction—requiring vigilance, expertise in advanced airway techniques, and close collaboration with surgical teams.

Given the complexity and frequency of difficult airways in this surgical subset, tracheal intubation must be approached with a thorough understanding of patient-specific risks, procedural implications, and available airway management strategies.

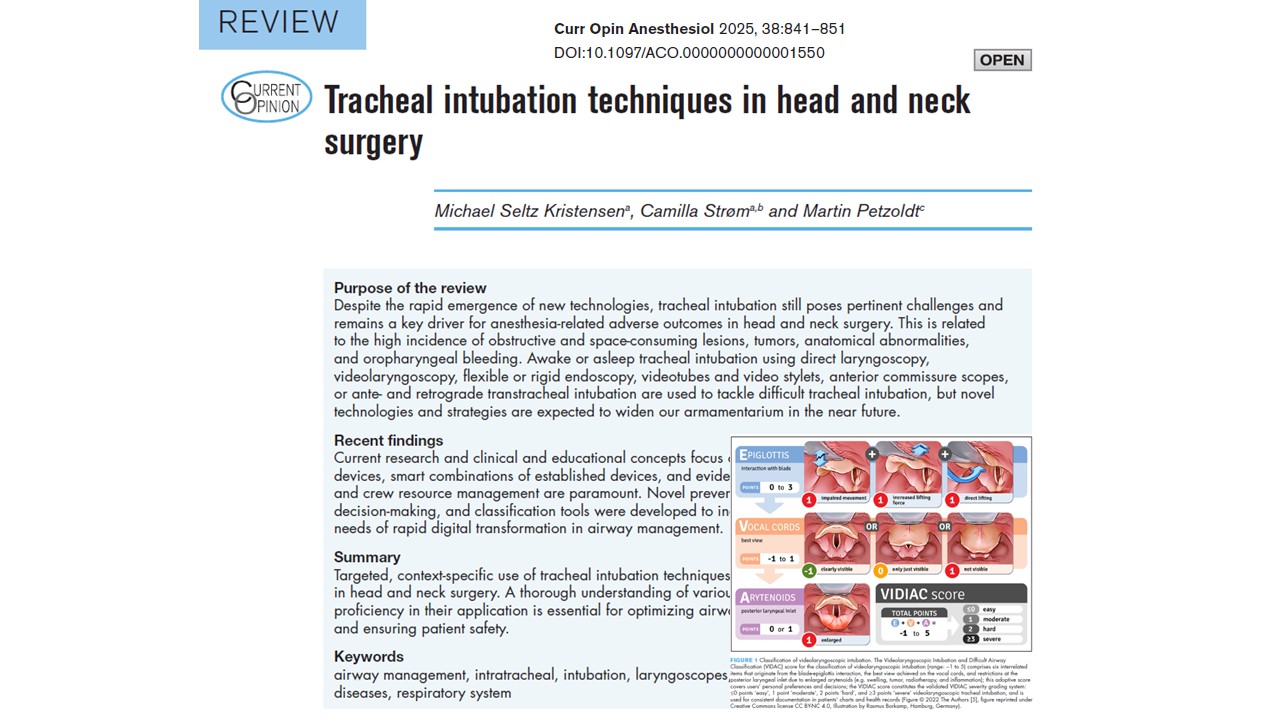

This comprehensive article, based on the review by Kristensen et al. (2025), explores current best practices in tracheal intubation for head and neck surgery, detailing preoperative evaluation, intubation techniques, rescue strategies, and perioperative planning. It empowers anesthesiologists to navigate these high-stakes cases with confidence and precision.

Understanding the unique challenges in head and neck airway management

Head and neck pathology is often associated with:

- Obstructive tumors involving the oral cavity, pharynx, or larynx.

- Edema, fibrosis, or scarring from prior surgery or radiation therapy.

- Trismus, reduced neck mobility, or limited mouth opening.

- Airway deviation or distortion from masses, trauma, or congenital anomalies.

These factors increase the likelihood of difficult mask ventilation, difficult laryngoscopy, and failed intubation, and may contraindicate conventional induction approaches.

Key risks in this population:

- Complete airway obstruction on induction

- Limited options for rescue ventilation

- Higher rates of emergency tracheostomy

- Need for a shared airway between an anesthesiologist and the surgeon

These realities demand meticulous preoperative airway assessment, anticipation of failure, and preparation for alternative plans, including awake techniques and front-of-neck access.

Preoperative evaluation and planning

Comprehensive airway assessment

A thorough evaluation should include:

- Mallampati score

- Mouth opening (interincisor gap)

- Neck mobility and jaw protrusion

- Thyromental and sternomental distance

- Presence of tumors, prior surgery, or radiation

- Symptoms of airway compromise (dyspnea, stridor, positional breathing difficulty)

When feasible, nasendoscopy offers invaluable information on vocal cord mobility, tumor bulk, and airway patency.

Imaging studies

- CT or MRI: Assess airway anatomy, tumor extent, tracheal deviation.

- 3D reconstruction: May aid in pre-surgical planning in complex distortions.

Risk stratification and decision-making

The decision between awake vs. asleep intubation should consider:

- Likelihood of difficult ventilation or intubation

- Tolerance for apnea

- Access to rescue techniques

- Presence of symptoms indicating a compromised airway

In borderline cases, multidisciplinary discussion is essential to select the safest approach.

Awake tracheal intubation: the gold standard in anticipated difficult airways

Awake intubation is considered the safest method in patients with a high risk of airway obstruction or intubation failure. It maintains spontaneous ventilation and allows continuous patient cooperation.

- Nebulized lidocaine (4%): For nasal/oral cavity anesthesia.

- Lidocaine sprays/gels: Direct mucosal application.

- Transtracheal injection: For subglottic anesthesia.

- Superior laryngeal nerve blocks: Improve patient comfort.

Sedation considerations

- Use dexmedetomidine, remifentanil, or low-dose midazolam to maintain patient cooperation without compromising airway tone or ventilation.

- Avoid oversedation to preserve protective reflexes.

Preferred intubation methods

- Flexible bronchoscopy (FOB): Remains the standard.

- Video-assisted FOB: Improves visualization and success.

- Video laryngoscopes (VL): Useful when anatomy is partially favorable.

Awake techniques require patient preparation, local anesthetic expertise, and often additional personnel—but significantly reduce the risk of failed airway.

Asleep intubation: when appropriate and how to ensure safety

In patients with favorable airway anatomy or in specific urgent surgical contexts, asleep intubation may be a suitable option.

Optimizing asleep techniques

- Preoxygenate thoroughly and consider apneic oxygenation.

- Use video laryngoscopy as the first-line device.

- Have rescue devices (e.g., supraglottic airways, bougies) immediately available.

- Use short-acting induction agents (e.g., propofol, remifentanil) for rapid emergence if needed.

Always formulate a Plan B and Plan C, including readiness for front-of-neck access if ventilation fails.

Advanced intubation techniques and devices

- First-line device in many head and neck surgeries.

- Allows for an indirect glottic view with reduced need for alignment.

- Reduces the number of intubation attempts and improves the first-pass success rate.

Flexible bronchoscopy (FOB)

- Ideal for distorted anatomy and awake intubation.

- Can be used in combination with supraglottic airway placement (“Aintree technique”).

Intubating supraglottic airways

- Devices like i-gel or LMA Fastrach allow for oxygenation and guided intubation.

- Particularly useful as rescue tools after failed laryngoscopy.

Optical stylets and bougies

- Provide alternative means of guiding tubes through obscured airways.

- Require operator familiarity and careful use to avoid trauma.

Rigid indirect laryngoscopes (e.g., Bullard)

- Useful in patients with minimal mouth opening or an anterior larynx.

Surgical airways: when and how

Tracheostomy and cricothyrotomy

- It should be considered preemptively in patients with unmanageable airways or severe obstruction.

- It may be performed under local anesthesia in fully awake patients.

- It should be discussed with the surgical team in preoperative planning.

Elective tracheostomy

- Considered for extensive head and neck resections with anticipated prolonged airway compromise.

Emergency front-of-neck access (eFONA)

- Must be part of the airway plan in case of “cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate” scenarios.

- All providers must be trained and equipped for cricothyrotomy techniques.

Special populations and considerations

Oncologic airway obstruction

- Patients with large tumors may require awake tracheostomy under local anesthesia.

- Inhalation induction while maintaining spontaneous ventilation may be used cautiously in cooperative patients.

Radiated neck

- Anticipate the development of fibrosis, poor tissue planes, and an increased risk of bleeding.

- VL and FOB are preferred over blind or forceful techniques.

Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

- Higher incidence of difficult mask ventilation and rapid desaturation.

- Apneic oxygenation and ramped positioning improve outcomes.

Team-based approach and communication

Optimal outcomes in head and neck airway management require:

- Preoperative team briefings include anesthesia, surgery, and nursing.

- Simulation-based training for crisis scenarios.

- A checklist is used to ensure the availability of all airway devices and backup plans.

Regular interdisciplinary collaboration ensures all team members are prepared for routine and emergent airway scenarios.

Postoperative airway management

- Swelling, bleeding, and airway edema may evolve postoperatively.

- Extubation should be planned when the patient is fully awake and the criteria are met.

- In high-risk cases, delayed extubation in the ICU with an airway exchange catheter in place is advised.

- Always have plans and equipment for reintubation ready.

Conclusion

Airway management in head and neck surgery is a high-stakes, skill-intensive aspect of anesthetic practice. With patient safety as the ultimate priority, success hinges on comprehensive preoperative assessment, appropriate selection of intubation technique, and rigorous preparation for alternative strategies.

Awake tracheal intubation remains the cornerstone in anticipated difficult airways, while asleep approaches may be appropriate in select patients. Mastery of video laryngoscopy, flexible bronchoscopy, and surgical airway techniques is essential for all providers managing these complex cases.

As technology advances and evidence evolves, anesthesiologists must remain at the forefront—balancing innovation with clinical judgment, and maintaining seamless communication with surgical teams to ensure optimal outcomes in every case.

Read more in the full article in Current Opinion in Anesthesiology.

Kristensen MS, Strøm C, Petzoldt M. Tracheal intubation techniques in head and neck surgery. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2025 Dec 1;38(6):841-851.

Learn more about airway management techniques and penetrating neck injuries in our Anesthesiology Module on NYSORA 360—an essential learning resource for residents with up-to-date, practical guidance across perioperative care.