Learning objectives

- Difference between intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS)

- Recognize ACS and the pathophysiological consequences of ACS

- Management of ACS

Definition and mechanisms

- Normal intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) ranges between 0-5 mmHg while in critically-ill patients, an IAP of 5-7 mmHg is considered normal

- Intra-abdominal hypertension is defined as a sustained intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) ≥12 mmHg

- Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) is defined as IAP rises > 20 mmHg thereby leading to new organ dysfunction

- Abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) is calculated as the mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus the IAP

- A critically ill patient with high mortality & morbidity

Signs and symptoms

- Malaise

- Weakness

- Dyspnea

- Abdominal bloating

- Abdominal pain

- Hypoxia

- Hypercabia

- Oliguria

Etiology

Acute ACS

- Primary: due to injury or disease in the abdominopelvic region (e.g., pancreatitis, abdominal trauma)

- Secondary: does not originate in the abdomen or pelvis (e.g., fluid resuscitation, sepsis, burns)

Chronic ACS

- In association with peritoneal dialysis or chronic ascites

Artificially raised IAP

- External compression, for example, prolonged prone positioning for spinal surgery with insufficient provision for abdominal movement

Risk factors

| Diminished abdominal wall compliance | Acute respiratory failure, especially with elevated intrathoracic pressure Abdominal surgery with subjectively tight primary closure Major trauma/burns Prone positioning, head of bed elevated > 30° High BMI, central obesity |

| Increased intra-luminal contents | Gastroparesis Ileus Colonic pseudo-obstruction |

| Increased abdominal contents | Hemoperitoneum/pneumoperitoneum Ascites/liver dysfunction |

| Capillary leak/fluid resuscitation | Metabolic acidosis ( pH < 7.2) Hypotension Perioperative hypothermia Polytransfusion (>10 units of blood/24 h) Coagulopathy (platelets < 55 000 mm-3, prothrombin time > 15 s, partial thromboplastin time > 2 times normal, or international standardized ratio >1.5) Massive fluid resuscitation (> 5 litre/24 h) Pancreatitis Oliguria Sepsis Trauma Burns Damage control laparotomy |

Pathophysiological effects of raised IAP

| Central nervous system | Increased intra-cranial pressure |

| Cardiovascular system | Increased systemic vascular resistance Pulmonary vascular resistance Decreased venous return with concomitant venous congestion |

| Gastrointestinal and hepatic system | Decreased coeliac, mesenteric, hepatic and hepatic portal blood flow Increased oedema, bacterial translocation and liver dysfunction |

| Renal system | Increased renal tubular pressure and urinary obstruction Decreased renal blood flow and urine output |

| Respiratory system | Increased ventilation-perfusion mismatch, ventilatory pressure, basal atelectasis and PaCO2 Decreased chest wall and pulmonary compliance and PaO2 |

Diagnosis

- Indirect measurement of IAP using intragastric, intracolonic, intravesical (bladder), or inferior vena cava catheters

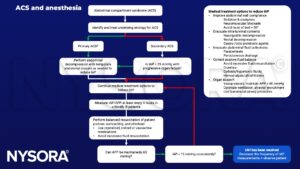

Management

- Patients with two or more risk factors should have IAP monitoring

- Treatment:

- Regimens lowering IAP

- Open the abdominal wound and perform a temporary closure of the abdominal wall with mesh or a plastic bag (Bogota bag)

- Regiments aiming at organ support

- Keep abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) (systemic blood pressure – intra-abdominal pressure) > 60mmHg

Keep in mind

- Consequences of decompression:

- Sudden ↓ cardiac output & SVR

- Reperfusion: risk of systemic acidosis & hyperkalemia

- Possible fatal arrhythmia & arrest

- Sudden change in respiratory compliance (avoid overventilation)

- Avoid bradycardia (preload is compromised & CO may be heart rate dependent)

- Maintain high preload particularly once decompressed

Suggested reading

- Neil Berry, Simon Fletcher, Abdominal compartment syndrome, Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain, Volume 12, Issue 3, June 2012, Pages 110–117.

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Skouri HN, et al. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure in acute decompensated heart failure: a potential contributor to worsening renal function? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(3):300-306.

We would love to hear from you. If you should detect any errors, email us customerservice@nysora.com