Learning objectives

- Describe the overall mechanisms and common causes of status epilepticus

- Describe the signs of status epilepticus

- Prevent status epilepticus

- Manage status epilepticus

Definition & mechanisms

- Status epilepticus is defined as more than 30 minutes of either 1) continuous seizure activity or 2) two or more sequential seizures without full recovery of consciousness between seizures

- Cerebral damage is more likely if the seizure is prolonged

- There are lots of different types of seizures and not all of them involve obvious convulsive activity

- Epilepsy can occur at any age but is commonly diagnosed in those aged below 20 or over 65 years

- First stage is characterized by an increase in:

- Cerebral metabolism

- Blood flow

- Glucose and lactate concentration

- Compensatory mechanisms:

- Massive catecholamine release

- Raised cardiac output

- Hypertension

- Increased central venous pressure

- After 30-60 min, compensatory mechanisms fail:

- Hypoxia

- Hypoglycemia

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Cerebral edema

- Hyponatremia

- Potassium imbalance

- Evolving metabolic acidosis

- Consumptive coagulopathy

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Multi-organ failure

Etiology

- Acute

- Stroke

- Metabolic abnormalities

- Hypoxia

- Systemic infection

- Anoxia

- Trauma

- Traumatic brain injury

- Drug overdose

- CNS infection

- CNS hemorrhage

- Chronic

Signs & symptoms

Status epilepticus can present in several forms:

- Convulsive: unresponsiveness and tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic movements of the extremities

- Non-convulsive: prolonged seizure activity evidenced by epileptiform discharges on EEG, change in behavior or cognition in some patients

- Electrographic: commonly used for comatose patients who show electrographic evidence of prolonged seizure activity

Diagnosis

- Based on history and clinical examination

- Often present either actively convulsing or minimal time between clustered seizures

Prevention

- Seizure detection based on EEG and immediate treatment

- In patients with a history of well-controlled epilepsy, avoid disruption of antiepileptic medication perioperatively

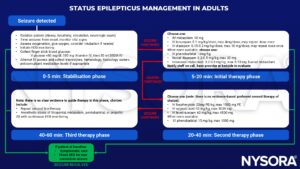

Management

Status epilepticus medications: Overview

Rescue benzodiazepines

| Medication | Dose range (max dose) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| IV lorazepam | 0.05-0.1 mg/kg/dose (2-4 mg) | May repeat dose once |

| Rectal diazepam | 0.2-0.5 mg/kg (20 mg) | Age 6 months - 5 years: 0.5 mg/kg Age 6-12 years: 0.3 mg/kg Age 12+ years: 0.2 mg/kg |

| Nasal midazolam | 0.2-0.3 mg/kg (5-10 mg) | <40 kg: 0.2-0.3 mg/kg >40 kg: give 10 mg (max dose), half the dose in each nostril |

| IM midazolam | 0.2-0.3 mg/kg (5-10 mg) | <13 kg: 0.2-0.3 mg/kg 13-40 kg: give 5 mg >40 kg: give 10 mg (max dose) |

| IV diazepam | 0.15-0.3 mg/kg (10mg) | Shorter duration compared to lorazepam Higher risk for respiratory depression |

Tier 2 medications

| Medication | Dose range (max dose) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Fosphenytoin | 20 mg PE/kg (1500 mg) | Drug levels quickly available for titration Avoid if known generalized epilepsy or Dravet syndrome Beware of hypotension and bradycardia Tissue extravasation is potentially dangerous |

| Levetiracetam | 60 mg/kg (4500 mg) | Also effective for myoclonic seizures |

| Valproic acid | 40 mg/kg (3000 mg) | Effective in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, myoclonic status and absence status Caution in patients with liver dysfunction and select metabolic diseases (e.g., POLG1) |

| Phenobarbital | 10-20 mg/kg (1000 mg) | Drug of choice in newborns Beware of hypotension and respiratory depression May use in adults if previously used with status due to missed or held doses |

| Lacosamide | 5-10 mg/kg (400 mg) | Caution with cardiac issues, can prolong PR interval Use if previously used and status due to missed or held doses |

Suggested reading

- Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, et al. Evidence-Based Guideline: Treatment of Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Children and Adults: Report of the Guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16(1):48-61.

- Betjemann JP, Lowenstein DH. Status epilepticus in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(6):615-624.

- Perks A, Cheema S, Mohanraj R. Anaesthesia and epilepsy. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2012;108(4):562-71.

We would love to hear from you. If you should detect any errors, email us at customerservice@nysora.com