Epidural Blood Patch: How To

In recent years, the epidural blood patch (EBP) has emerged as the “gold standard” for treatment of postdural puncture headache (PDPH).

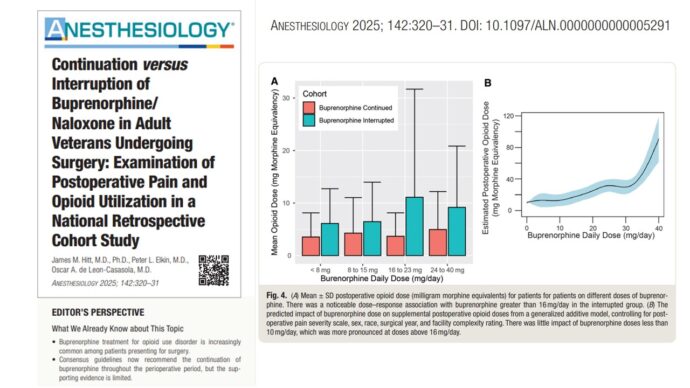

Postdural puncture headache infographic.

Although the mechanism of action of the EBP is not entirely clear, it seems to be connected to the prevention of further loss of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) when a clot forms over the defect in the meninges, and to the tamponade effect with cephalad displacement of CSF (the “epidural pressure patch”).

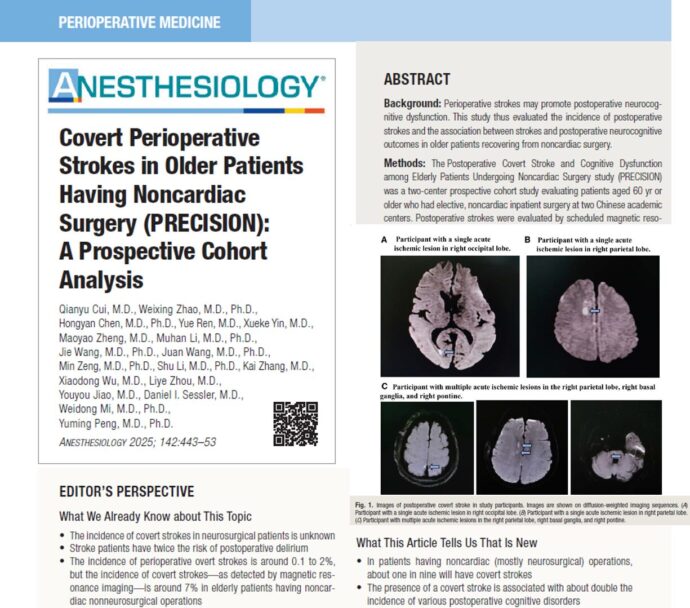

Epidural blood patch infographic.

How the EBP applies to individual cases depends on various factors, such as the length and severity of the headache and the associated symptoms, the type and gauge of the original needle used, and the wishes of the patient. The use of the EBP should be encouraged in patients who are experiencing accidental dural puncture (ADP) with an epidural needle and in those whose symptoms are categorized as severe (i.e., pain score >6 on a 1–10 scale). The informed consent for the EBP should include a discussion with the patient concerning the common and serious risks to be considered, the actual success rate, and the side effects anticipated. In addition, the patient must be equipped with clear instructions for the provision of timely medical attention in the event that they experience a recurrence of the symptoms.

The procedure for the sterile injection of fresh autologous blood near the previous dural puncture is as follows:

Epidural blood patch procedure:

- First obtain the written informed consent of the patient.

- Establish the IV access.

- Position the patient for epidural: Lateral decubitus may be more comfortable than sitting.

- Place the epidural needle into the epidural space at or below the level of the previous meningeal puncture using a standard sterile technique.

- Collect 20 mL of fresh autologous venous blood using a sterile technique.

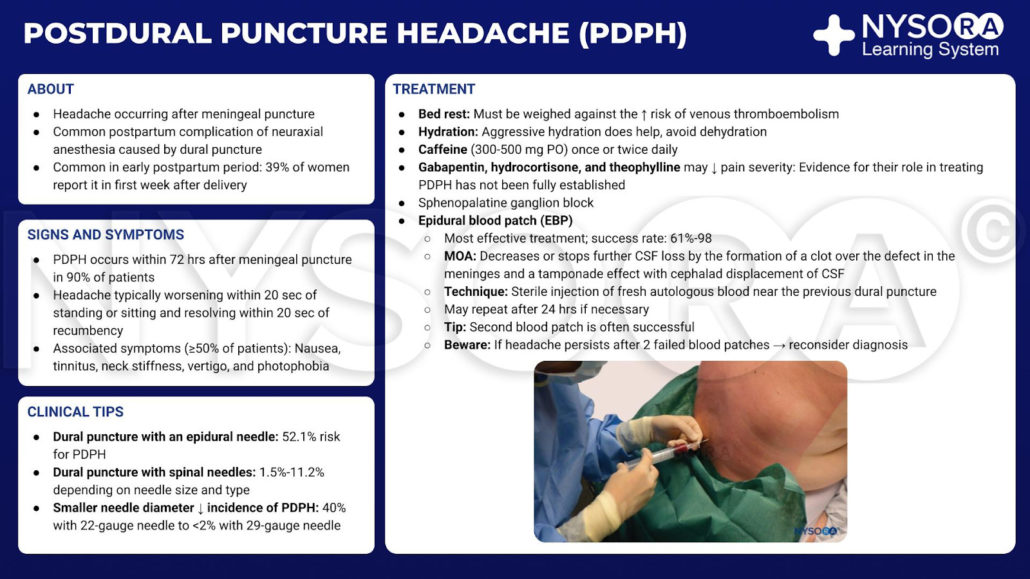

- Immediately inject the collected blood through the epidural needle (see image below) until the patient reports fullness or discomfort in the back, buttocks, or neck, whichever comes first.

- Keep the patient in a recumbent position for 1-2 hours. An IV infusion of 1 L crystalloid may be used to alleviate the headache until the EBP begins to take effect.

Blood patch. Administration of an epidural blood patch using 20 mL of freshly drawn blood. The blood is injected until 20 mL are reached or the patient perceives significant pain or pressure in the back, whichever comes first.

Instructions for discharge:

- Advise the use of over-the-counter analgesics (i.e., acetaminophen, ibuprofen) when necessary for any mild residual discomfort.

- Prescribe stool softeners or cough suppressants if indicated.

- Avoid lifting, straining, or air travel for 24 hours.

- Provide instructions on how to contact anesthesia personnel for in the case where relief has not been sufficiently effective, or if symptoms return.

Contraindications to the EBP are similar to those of any epidural needle placement: coagulopathy, systemic sepsis, fever, infection at the site, and patient refusal. Minor side effects are common following the EBP. Patients should be warned of the possibility of aching in the back, buttocks, or legs, as this is reported by around 25% of patients. Other mild and commonly reported after effects include transient neckache, bradycardia, and slight temperature elevation.

The EBP has been sufficiently proven to be safe, mainly through extensive clinical experience . The risks are comparable with other epidural procedures, and include infection, bleeding, nerve damage, and ADP. Although some patients may develop temporary back and lower extremity radicular pain, as previously stated, these complications are uncommon. With the correct technique, complications due to infection are rare. In general, the fact that a patient has previously undergone the EBP treatment does not appear to have significant impact on the success of future epidural interventions, but case reports have suggested that the EBP may occasionally result in clinically significant scarring. Serious complications secondary to the EBP do occur, but these have usually been reported in isolated cases in which the procedure has deviated from standard practice.