Mastery of gastric ultrasound – Identifying intraluminal fluid content

In our previous post, we covered the basics of identifying fluid content inside the stomach. This knowledge is often essential for determining the risk of emergency surgeries, such as aspiration during anesthesia. Fluid content can result from both internal (endogenous) and external (exogenous) factors, and understanding how to differentiate between high-risk and low-risk gastric content is vital for effective patient management.

Let’s briefly recap the case we explored:

Case recap:

A 40-year-old male with a wrist fracture came into the emergency department. He had consumed a drink approximately three hours before his admission. Given that he required emergency surgery, a gastric ultrasound was performed to assess potential aspiration risk. This ultrasound revealed fluid content in the stomach.

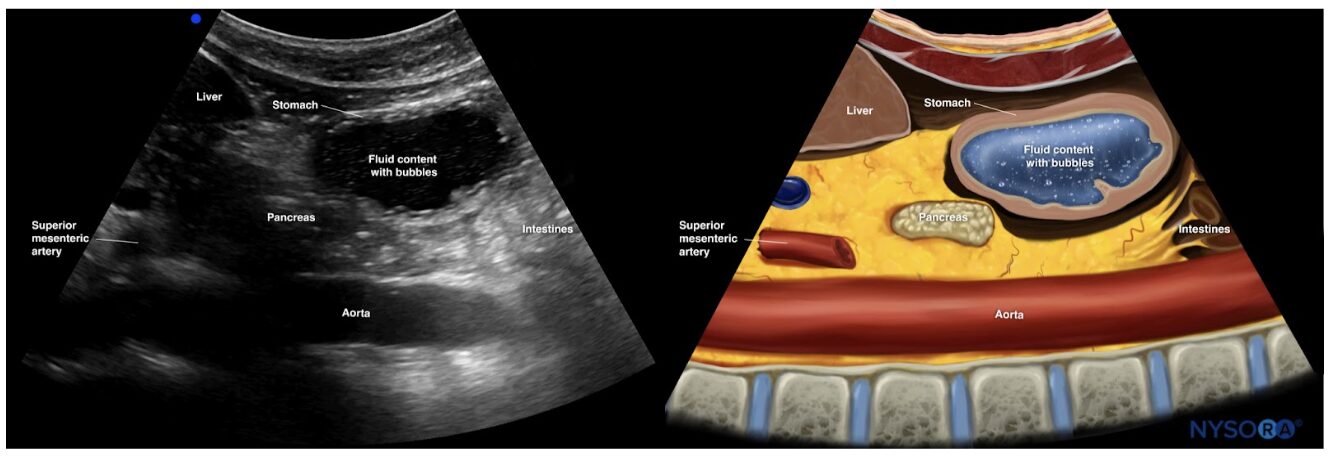

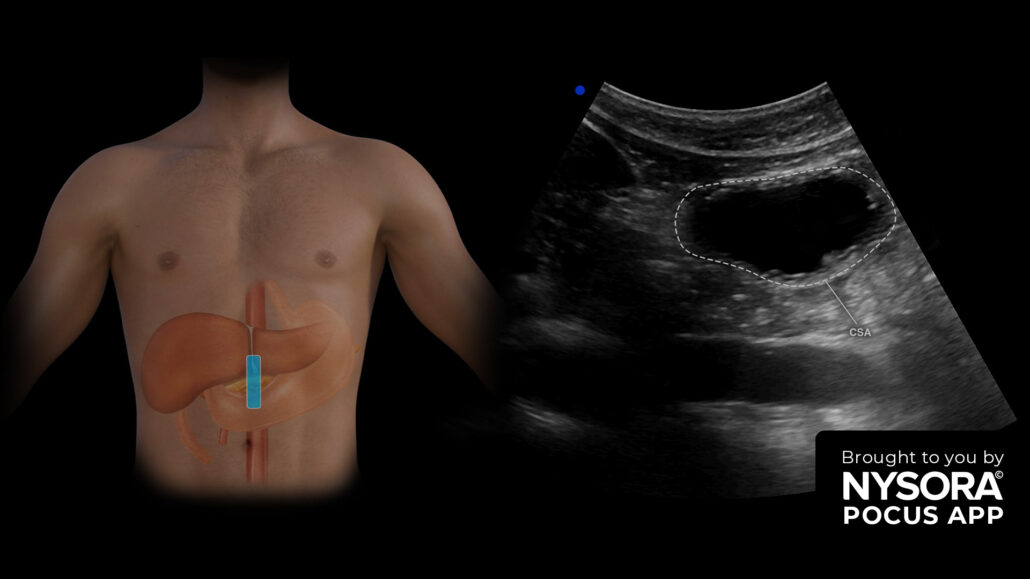

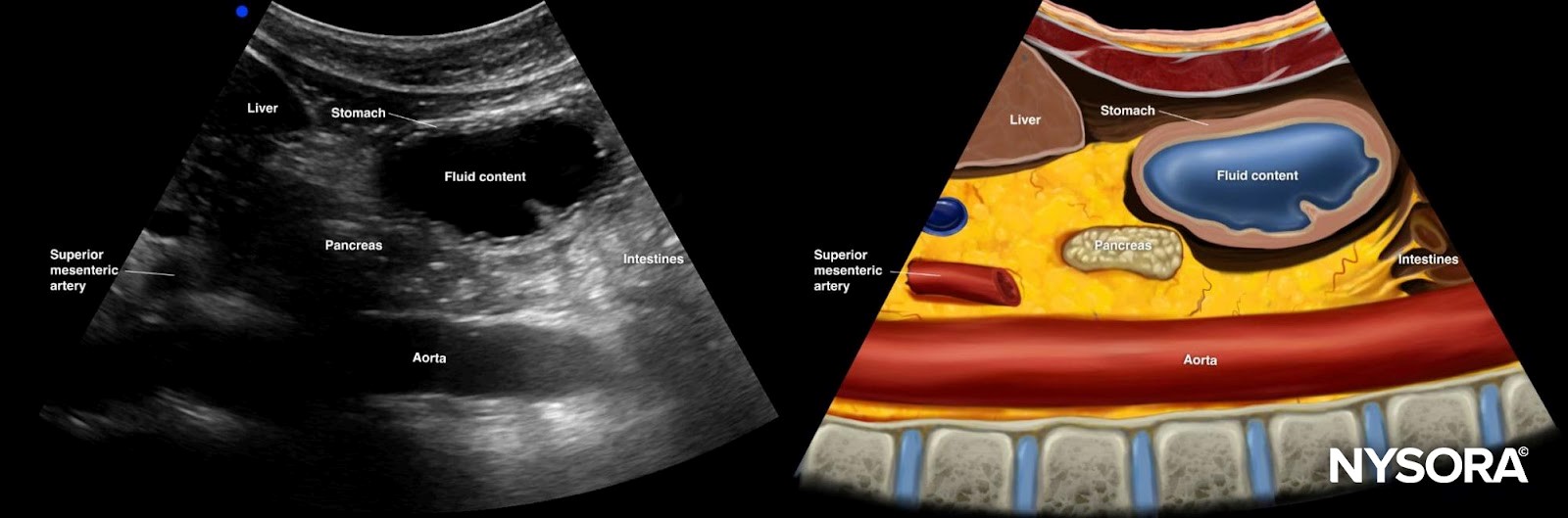

Ultrasound and Reverse Ultrasound Anatomy of a stomach with fluid content

This post will go deeper into:

- The causes of fluid content in the stomach

- The use of ultrasound to assess aspiration risk

- A tutorial on distinguishing between a high- and low-risk stomach using Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS)

What causes endoluminal gastric fluid?

Gastric fluid content can result from numerous factors:

- Delayed gastric emptying: This may be due to stress, medications like opioids, or underlying medical conditions.

- Non-compliance with fasting protocols: Some patients may have inadvertently eaten or drunk fluids before surgery.

- Gastric secretions: The stomach continuously produces fluids, which can contribute to its fluid content.

Differentiating high- and low-risk stomachs using ultrasound

When using ultrasound to assess fluid content in the stomach, the antrum’s cross-sectional area (CSA) must be measured in the right lateral decubitus position. This measurement helps clinicians determine whether the stomach contents pose a high or low risk of aspiration.

Step-by-step process for measuring fluid content

- Supine position: Start by assessing the stomach while the patient lies on their back. This will help define the type and amount of content.

- Clear fluid: Appears anechoic on the ultrasound image.

- Non-clear fluid (e.g., milk or suspensions): Appears hyperechoic, indicating denser content.

- Right lateral decubitus position: If clear fluid or an empty stomach is visualized in the supine position, further assessment is required in this position.

- Grade 0 (empty stomach): If no content is visualized in the lateral decubitus position, the stomach is empty.

- Grade 1 (low risk): If fluid content is visualized and calculated to be less than 1.5 mL/kg, the patient is considered to have fasted and is at low risk for aspiration.

- Grade 2 (high risk): If fluid content exceeds 1.5 mL/kg, the patient is considered at high risk for aspiration.

Formula for estimating gastric volume

To estimate the volume of gastric content, use the following formula:

Gastric volume (mL)= 27.0 + (14.6 × CSA of antrum in right lateral decubitus) − (1.28 × age)

Where:

- CSA: Cross-sectional area of the antrum measured in square centimeters.

- Age: The patient’s age in years.

If the gastric volume exceeds 1.5 mL/kg, the stomach is considered full and poses a high aspiration risk. If the volume is below this threshold, it is compatible with fasting and poses low risk.

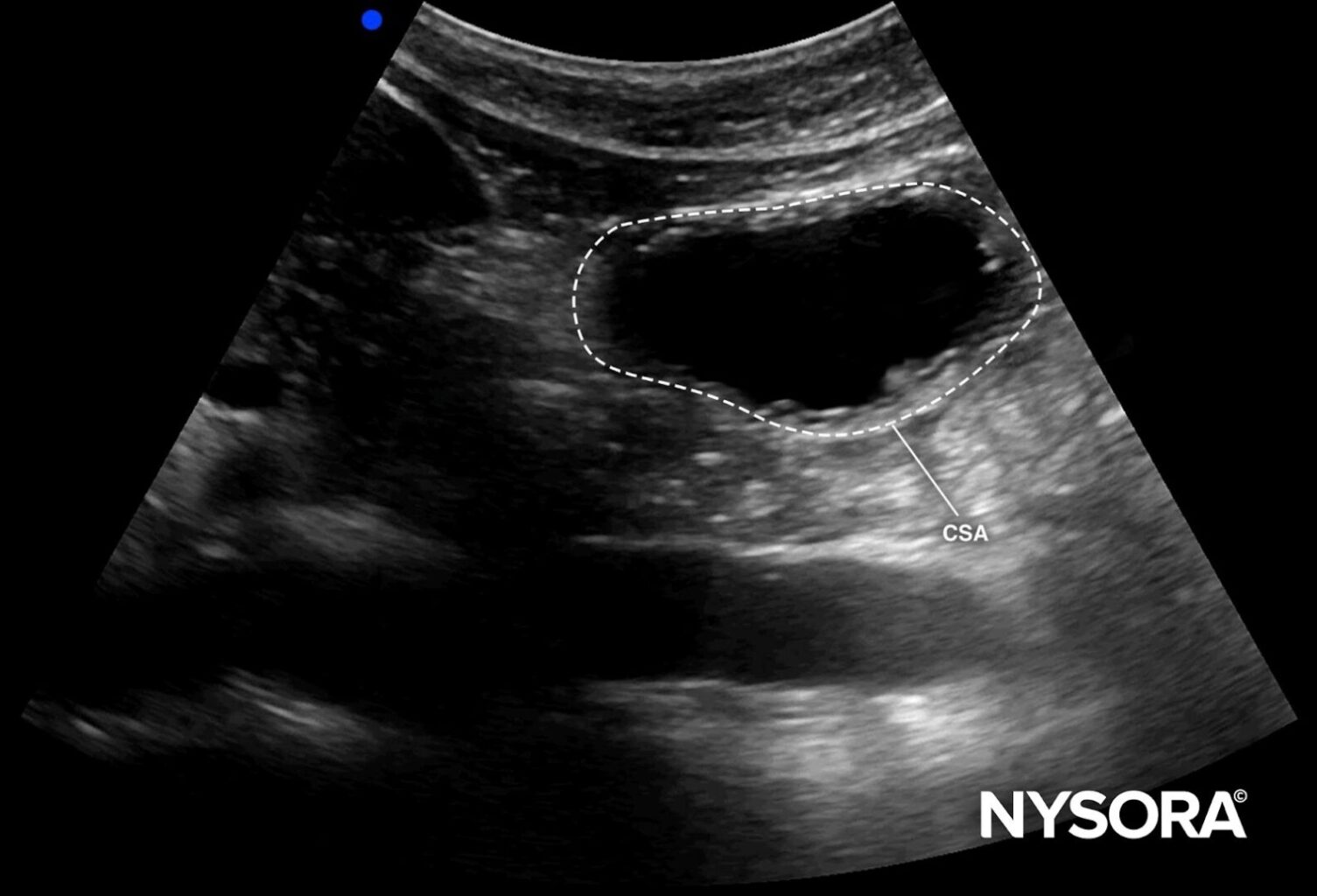

Measuring the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the antrum

To measure the CSA:

Trace the outer layer of the antrum (serosa) in the right lateral decubitus position.

- If your ultrasound machine has a free tracing tool, use it to outline the area directly.

- If not, calculate the CSA using the formula for the area of an ellipse:

CSA (cm²) = (anteroposterior diameter × craniocaudal diameter × π)/4

Ensure there are no peristaltic movements while measuring, as these can interfere with accuracy.

Cross-sectional area of the antrum.

Ultrasound appearance of fluid in the stomach

- Clear fluid: As mentioned, clear fluids appear anechoic on the ultrasound. This is common with water or certain types of gastric secretions.

- Non-clear fluids: Fluids like milk or gastric suspensions appear hyperechoic. They may appear more solid and bright white on the ultrasound screen.

“Starry night” appearance

One interesting phenomenon often observed with carbonated beverages is the “starry night” effect. This occurs when bubbles are present within the fluid content, creating a distinct visual pattern of tiny, bright, scattered spots across the anechoic fluid. While transient, this pattern helps identify recent ingestion of carbonated liquids.

Quick tips for accurate assessment

- Ensure correct positioning: Always assess the stomach in supine and lateral decubitus positions.

- Fluid type matters: Distinguish between clear and non-clear fluids to determine whether recent ingestion of dense fluids is likely.

- Utilize decision tables: Quick reference guides and decision tables can be used to cross-check CSA values and patient age for a faster estimation of gastric volume.

Conclusion

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) offers a highly effective, noninvasive method to assess fluid content in the stomach and determine the risk of aspiration during surgery. Understanding the distinction between high- and low-risk gastric content is crucial for patient safety, particularly in emergency situations.

By following the step-by-step guidelines, clinicians can enhance their diagnostic capabilities and make more informed decisions about airway management in patients with gastric fluid content.

Stay ahead of the curve and improve your POCUS skills with NYSORA’s POCUS App, designed to broaden your clinical expertise.

Transform your practice with the power of POCUS using NYSORA’s POCUS App. Enhance your skills, broaden your diagnostic capabilities, and provide outstanding patient care. Experience the difference today – Download the app HERE.