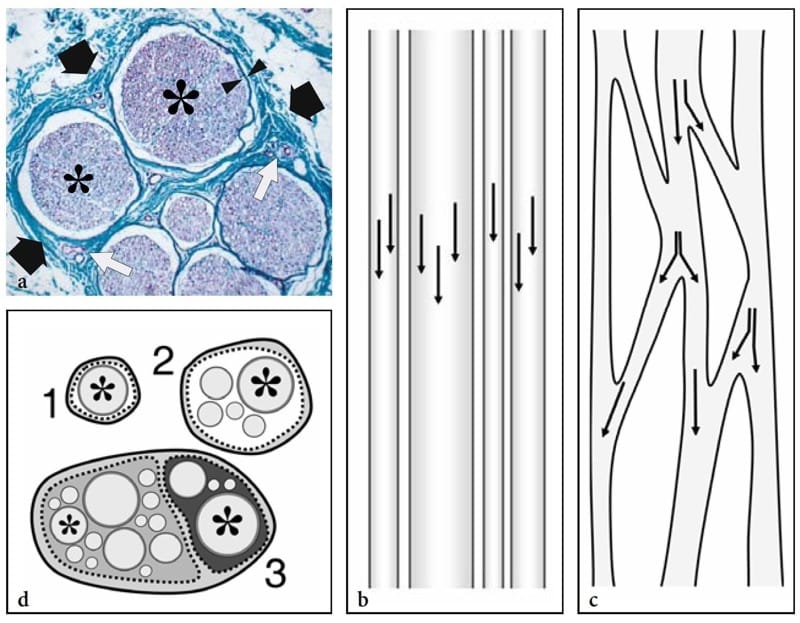

1. HISTOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS

From the histologic point of view, nerves are round or flattened cords, with a complex internal structure made of myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers, containing axons and Schwann cells grouped in fascicles (Fig. 1a) (Erickson 1997). Along the course of the nerve, fibers can traverse from one fascicle to another and fascicles can split and merge. Based on the fascicular arrangement, two theories have been hypothesized to explain the internal architecture of a nerve: the “cable” and the “plexiform” models (Stewart 2003). The first states that nerves are cable-like structures, in which fascicles run separately throughout the entire nerve length (Fig. 1b). The second asserts that fascicles alternate splitting, branching, and rejoining along the course of the nerve trunk (Fig. 1c). In fact, nerves have both cable and plexiform arrangement of the fascicles depending on the level of examination. In their more proximal portion (e.g., brachial plexus), a plexiform organization of the fascicles predominates. More distally (e.g., median nerve), nerves present a cable-like structure with high degree of somatic organization (e.g., sensory and motor fibers for a specific area of the skin or muscle contained in the same fascicle) (Stewart 2003). The nerve tissue is embedded in a series of connective tissue layers.

A closer look at the nerve sheaths demonstrates an external sheath – the outer epineurium – which surrounds the nerve fascicles. Each fascicle is invested in turn by a proper connective sheath – the perineurium – which encloses a variable number of nerve fibers and is responsible for the “blood-nerve” barrier. Then, the individual nerve fibers are invested by the endoneurium. The connective tissue intervening between the outer nerve sheath and the fascicles is commonly referred to as the interfascicular epineurium (internal epineurium), as opposed to the outer epineurium which surrounds the entire nerve trunk. Generally speaking, the amount of connective tissue of the epineurium is more abundant in large multifascicular nerves and in regions in which the nerve is mobile across joints (Delfiner 1996). This thickening of the connective tissue seems to provide more cushioning for the nerve and, therefore, more resistance to compression injury (Delfiner 1996). Externally, the outer (external) epineurium is continuous with the mesoneurium, which is made up of loose areolar tissue. This latter structure is credited with not only supplying the framework for the blood supply entering the nerve, but also making the excursion of the nerve in its bed easier without traction on its blood supply during joint motion (George and Smith 1996).

Nerves have a prominent vascular supply to ensure their continuous supply of local energy required for impulse transmission and axonal transport. The vascular supply is formed by an interconnected system of perineural vessels that course longitudinally in the external epineurium and branch among the fascicles (endoneural vessels).

Figure 1. a–d. Nerve histology. a Histologic cross-sectional view of the human sural nerve (black arrows) reveals some nerve fascicles (asterisks) of different size containing nerve tissue (violet) with collections of axons, myelin sheaths, and Schwann cells. Individual fascicles are invested by a thin sheath – the perineurium (arrowheads) – and are separated from each other by a loose connective tissue envelope – the epineurium (green) – containing small intraneural vessels (white arrows). Specimen stained using the van Gieson procedure (original magnification ×150). b,c Schematic drawings of a long-axis view through the nerve trunk illustrate the models of fascicular organization. Arrows indicate the axonal path. b In the “cable model,” the fascicles run parallel to the nerve axis without axonal exchange. c In the “plexiform model,” fascicles split and rejoin in various combinations with axons intermingling from one to another. d Schematic drawing of a cross-sectional view of the monofascicular (1), oligofascicular (2), and polyfascicular (3) nerve models. In complex motor and sensory nerves (3), fascicles (asterisks) are of different size and may be grouped in function-related areas within the nerve. This drawing (3) recalls the structure of the sciatic nerve, in which the nerves fibers for the tibial nerve (light gray) and for the peroneal nerve (dark gray) remain grouped tightly throughout the course of the nerve, even proximally.

2. NORMAL US ANATOMY AND SCANNING TECHNIQUE

Thanks to the latest generation of high-frequency “small parts” transducers and compound technology, US has become a well-accepted and wide-spread imaging modality for evaluation of peripheral nerves. The improved performance of these transducers has made it possible to recognize subtle anatomic details at least equal to or even smaller than those depicted with surface-coil MR imaging and to depict a wide range of pathologic conditions affecting nerves (Martinoli et al. 1999; Keberle et al. 2000; Beekman and Visser, 2004). Apart from the availability of high-end technology, nerve US requires thoughtful knowledge of anatomic details and close correlation of imaging findings with the patient’s clinical history and the results of electrophysiologic studies. With these credentials, US provides low-cost and noninvasive imaging, speed of performance, and important advantages over MR imaging, including a higher spatial resolution and the ability to explore long segments of nerve trunks in a single study and to examine nerves in both static and dynamic states with real-time scanning.

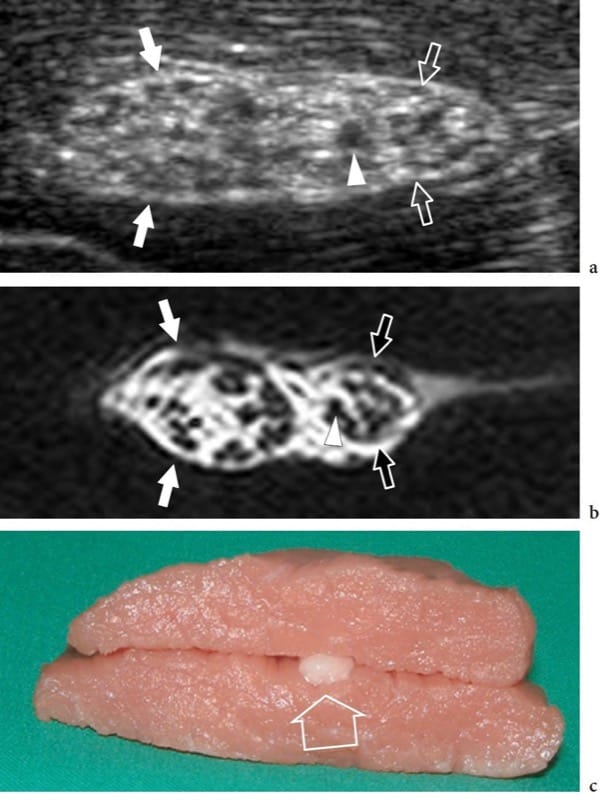

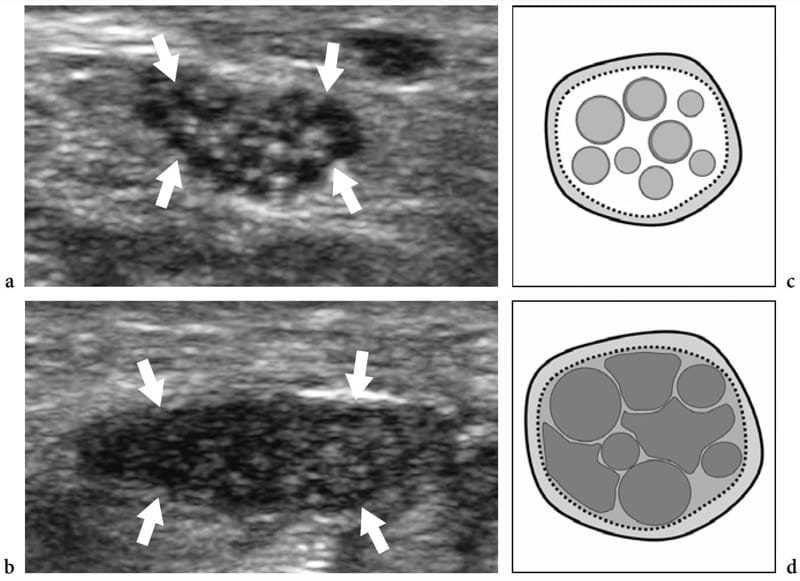

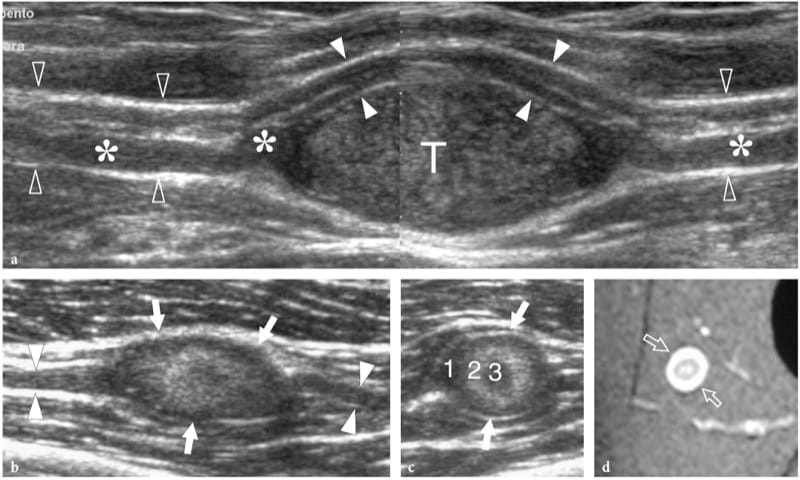

The US appearance of normal nerves is fairly uniform, closely reflecting their histologic composition (Fig. 2) (Silvestri et al. 1995). On short-axis planes, US demonstrates nerves as honeycomb-like structures composed of hypoechoic spots embedded in a hyperechoic background in which the hypoechoic structures correspond to the fascicles that run longitudinally within the nerve, and the hyperechoic background relates to the interfascicular epineurium (Figs. 2a, 3a) (Silvestri et al. 1995). This pattern somewhat resembles the section of an electric cable. On long-axis planes, nerves typically assume an elongated appearance with multiple hypoechoic parallel linear areas, which correspond to the neuronal fascicles that run longitudinally within the nerve, separated by hyperechoic bands (Fig. 3b) (Silvestri et al. 1995). In an individual nerve, the size and number of the fascicles may vary depending on the distance from site of origin, the amount of pressure to which the nerve is subjected, and the occurrence of nerve branching. In nerve bifurcations, for instance, the nerve trunk divides into two or more secondary nerve bundles, whereas fascicles enter only one of the divisional branches without splitting. The outer boundaries of nerves are usually undefined as they have a similar hyperechoic appearance to their connective envelopes, including the outer epineurium, the mesoneurium, and the surrounding loose connective spaces, all of which contain fat.

Figure 2. a–c. Nerve anatomy. In vitro a short-axis 12–5 MHz US image of the bovine sciatic nerve (arrows) with b correlative T1-weighted MR imaging demonstrates a honeycombed nerve echotexture made up of small rounded hypoechoic areas (arrowhead), the fascicles, that are embedded in a hyperechoic background, the epineurium. Observe the definite grouping of fascicles within the sciatic nerve for the tibial (white arrows) and the peroneal (open arrows) nerves. c The in vitro model was prepared by incorporating the nerve (open arrow) within muscle tissue.

Figure 3. a,b. Normal nerve echotexture. a Short-axis and b long-axis 15–7 MHz US images over the median nerve (open arrows) at the mid-forearm. In a, the nerve fascicles (white arrow) are depicted as well-circumscribed individual structures of different size separated by echogenic epineurium. In this segment, 11 fascicles are distinguished in the cross-sectional area of the median nerve. In b, the nerve fascicles appear as elongated hypoechoic bands (white arrows) that run parallel to each other. The internal epineurium (white arrowheads) separates them more clearly, while the external epineurium (open arrowheads) helps to define the outer boundaries of the nerve.

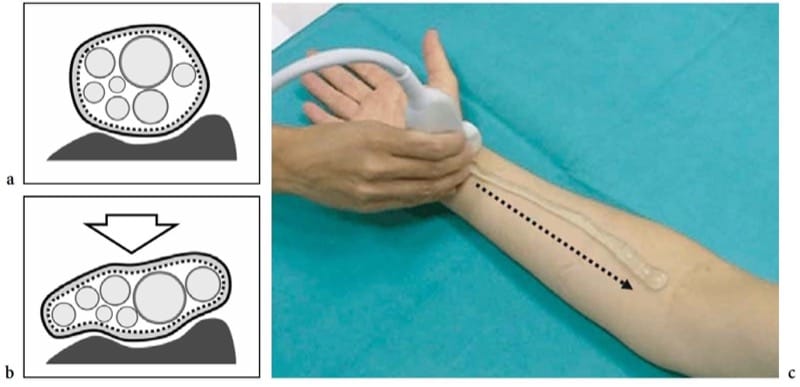

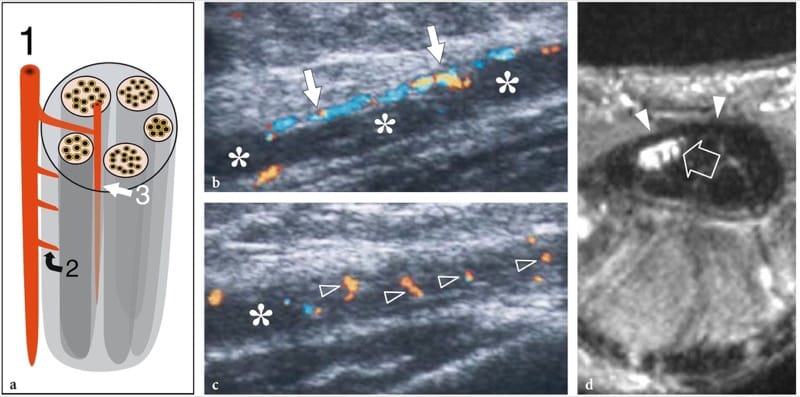

In normal states, color and power Doppler systems are, for the most part, unable to recognize the weak and small blood flow signals from the perineural plexus and the intraneural branches. Generally speaking, nerves are compressible and alter their shape depending on the volume of the anatomic spaces within which they run as well as on the bulk and conformation of the perineural structures (Fig. 4a,b). Even with slight pressure applied with the probe, they may be seen sliding over the surface of an artery or a muscle. As a general rule, each individual fascicle in a nerve runs independently of the others. Across synovial joints, they pass through narrow anatomic passageways – the osteofibrous tunnels that redirect their course. The floor of these tunnels consists of bone, whereas the roof is made of focal thickenings of the fascia – the retinacula that prevent dislocation and traumatic damage of the structures contained in the tunnel during joint activity (Martinoli et al. 2000b). When nerves cross tight passages, such as neural foramina and osteofibrous tunnels, subtle echotextural changes can be seen, with a more homogeneous hypoechoic appearance caused by tighter packing of the fascicles and local reduction in the volume of the epineurium (Sheppard et al. 1998).

A careful scanning technique based on the precise knowledge of their position and analysis of their anatomic relationships with surrounding structures is essential for recognizing peripheral nerves with US. Unlike other structures of the musculoskeletal system, nerves do not show anisotropic properties. Therefore, appropriate probe orientation during scanning is not needed to image them; however, systematic scanning in the short-axis plane is preferred for following the nerves contiguously throughout the limbs (Martinoli et al. 1999). Long-axis scans are less effective for this purpose because the elongated fascicles may be easily confused with echoes from muscles and tendons coursing along the same plane. Once detected, the nerve is kept in the center of the US image in its short axis and then followed proximally and distally, shifting the transducer up or down according to the nerve’s course. With this technique – which we can call the “lift technique” the examiner is able to explore long segments of a nerve in a few seconds throughout the limbs and extremities (Fig. 4c). If intrinsic or extrinsic nerve abnormalities are encountered during scanning, the US examination is then appropriately focused on the region of interest using oblique and longitudinal US scanning planes. Although all main nerves can be readily displayed in the extremities due to their superficial position and absence of intervening bone, depiction of the peripheral nervous system is not possible everywhere with US. In fact, most cranial nerves – except for the vagus – and the spinal accessory nerve (Giovagnorio and Martinoli, 2001; Bodner et al. 2002a), the nerve roots exiting the dorsal, lumbar and sacral spine, the sympathetic chains, and the splanchnic nerves in the abdomen cannot be visualized due to their course being to deep or interposition of bony structures. In addition, the perineural structures greatly influence nerve detection in the limbs and extremities. When nerves course deeply, as in obese patients, their evaluation can be difficult. As a general rule, nerves of the lower extremity run deeper than those of the upper extremity and are more difficult to visualize. Nerves coursing among hypoechoic muscles are detected easier than those surrounded by hyperechoic fat. Similarly, a nerve of a young physically active subject is better depicted than the same nerve examined in a subject with atrophic muscles.

Figure 4. a–c. Response to compression and nerve scanning technique. a,b Schematic drawings of the cross-sectional view of a nerve lying over a stiff surface (bone) a at rest and b during external compression (arrow). Due to the flexibility of the epineurial sheath, the nerve flattens, whereas the fascicles – which are noncompressible structures – redistribute according to the nerve shape changes. c Photograph shows the standard technique for examining nerves in the limbs. The short axis of the median nerve at the wrist is centered in the field of view of the US image. Then, the transducer is swept upward (dashed arrow) along the course of the nerve in the forearm. This technique, which we can call the “lift technique,” allow a simple and reliable evaluation of long nerve segments in a single sweep, excluding possible intrinsic and extrinsic abnormalities along the nerve path. The ability of US to follow the entire course of nerves in the limbs so quickly is a major advantage over MR imaging.

3. ANATOMIC VARIANTS, INHERITED AND DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES

Given the characteristic US appearance of normal nerves, some anatomic variants can be recognized with this technique. Among these, the proximal bifurcation of the median nerve at wrist has been extensively reported in the literature (Propeck et al. 2000; Iannicelli et al. 2000; Gassner et al. 2002). Similarly, some inherited and developmental anomalies of the peripheral nervous system, such as the fusiform enlargement of the median nerve by fibrofatty tissue (so-called fibrolipomatous hamartoma), the hypertrophy of nerves in Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome (Martinoli et al. 2002), and the focal enlargement of nerves in hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (Beekman and Visser 2002) can be recognized with US. In these disorders, US findings may contribute to the understanding of pathophysiology by noninvasively revealing some important morphologic information. Further work is, however, required to fully analyze the impact and reliability of US in this field.

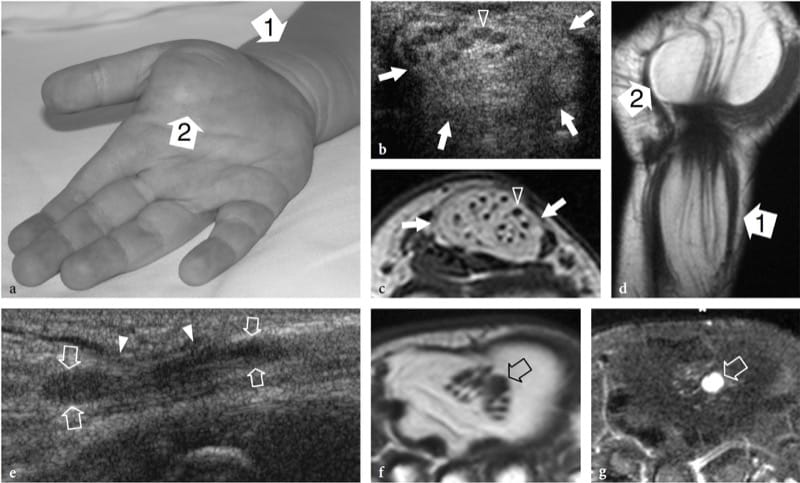

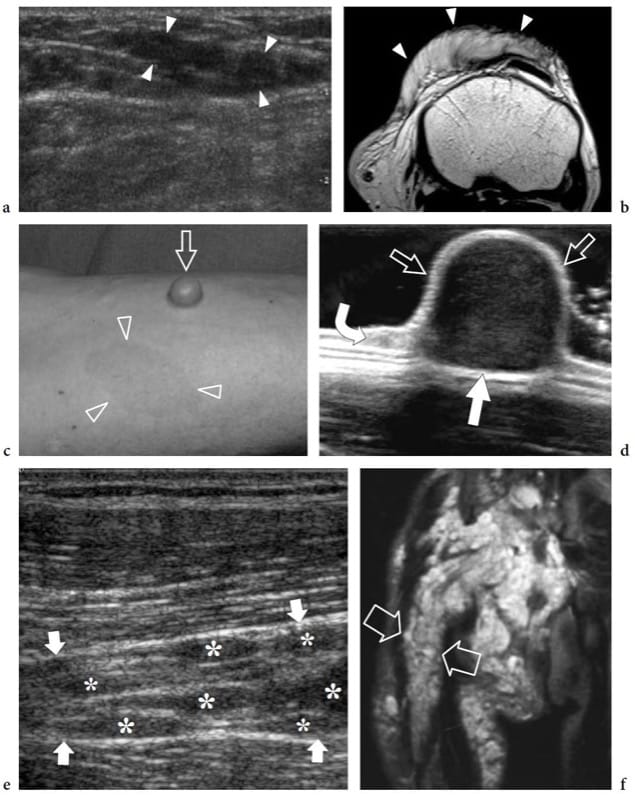

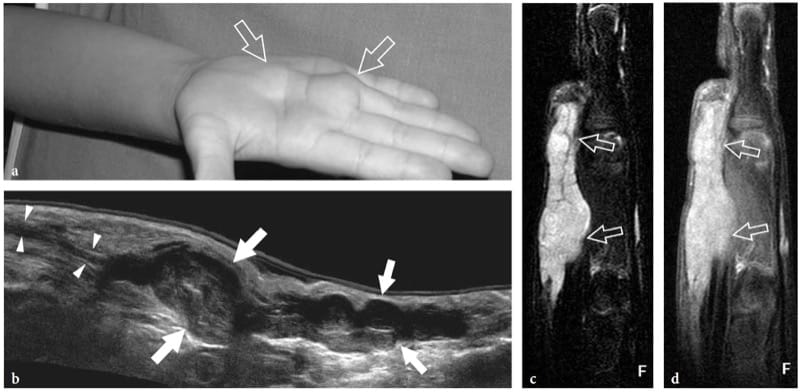

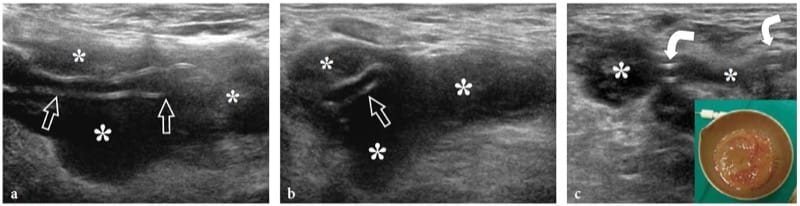

4. FIBROLIPOMATOUS HAMARTOMA

Fibrolipomatous hamartoma is a developmental tumor-like nerve disorder related to the hypertro-phy of mature fat and fibroblasts in the epineurium that often presents during early childhood. This condition – which is also referred to as neural fibrolipoma, perineural lipoma, fatty infiltration of the nerve, lipofibroma, or neural lipoma – has a definite predilection for the median nerve and its branches, with lower extremity involvement (plantar nerve, sciatic nerve) reported as being rare (Marom and Helms 1999; Wong et al. 2006). Fibrolipomatous hamartoma may be associated with local gigantism of an extremity, usually the hand or foot, related to bony overgrowth, fat proliferation in the soft tissues, and nerve-territory-oriented macrodactyly, characteristic of the condition known as macrodystrophia lipomatosa (Amadio et al. 1988; Murphey et al. 1999). The US appearance of fibrolipomatous hamartoma is pathognomonic of this entity, reflecting the morphology of the lesion. US demonstrates a striking fusiform enlargement of the median nerve at the distal forearm through the palm, characterized by an increased bulk of hyperechoic adipose tissue in the epineurium that surrounds and is interposed between normal-appearing fascicles (Fig. 5a–d) (Murphey et al. 1999; Chen et al. 1996). At the carpal tunnel level, the affected median nerve may become symptomatic earlier than other nerves due to its encroachment by the flexor retinaculum. In these instances, detection of nerve fascicles that appear focally swollen within the adipose mass indicates compression and the need for carpal tunnel release (Fig. 5e–g). Debulking of the mass may compromise the intraneural vasculature causing catastrophic motor and sensory deficits or an intense healing response that may further jeopardize function (Marom and Helms 1999).

Figure 5. a–g. Fibrolipomatous hamartoma. a Photograph of the right hand of a 3-year-old child presenting with mild symptoms of median neuropathy and diffuse soft-tissue swelling and tenderness extending from the distal radius (1) through the radial aspect of the palm (2). b Transverse 12–5 MHz US image obtained proximal to the carpal tunnel with correlative c transverse and d coronal T1-weighted MR images demonstrates abnormal fusiform enlargement of the median nerve (arrows). The nerve exhibits normal-appearing fascicles (arrowhead) interspersed with hyperechoic fat in the epineurium. There is close correlation between the US and MR imaging findings. In the coronal plane, MR imaging demonstrates abnormal predominant fat growth outside the confined space of the carpal tunnel. e Longitudinal 12–5 MHz US image at the carpal tunnel level identifies fusiform swelling of an individual fascicle (arrows) just deep to the flexor retinaculum (arrowheads). Corresponding transverse f T1-weighted and g fat-suppressed T2-weighted MR images confirm the presence of a single swollen T2-hyperintense fascicle (arrow), compared with the adjacent normal ones, possibly indicating a compressive abnormality. The patient experienced relief of symptoms postoperatively and the pain did not recur during 1 year of postoperative follow-up.

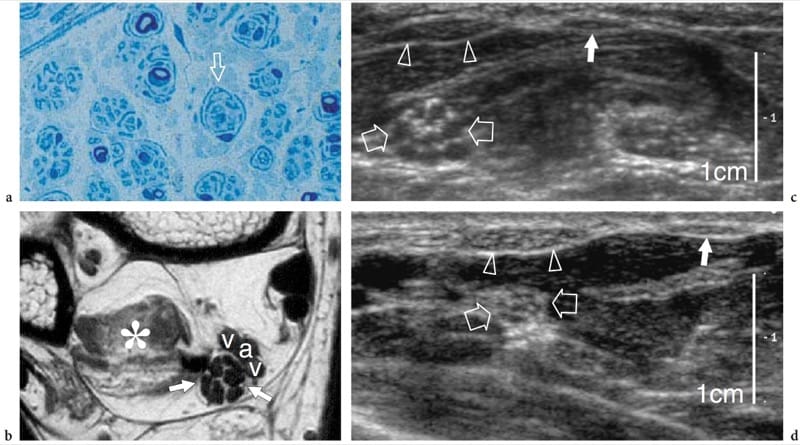

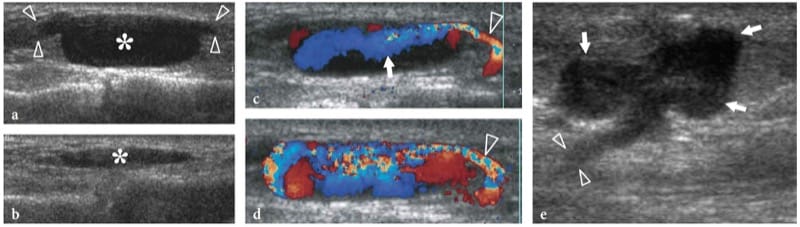

5. CHARCOT-MARIE-TOOTH DISEASE

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is a complex and heterogeneous group of inherited disorders of the peripheral nervous system, also known as hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies, that is characterized by hypertrophied peripheral neuropathy due to the abnormal growth (like an onion bulb) of Schwann cells (Fig. 6a,b). The most common clinical features include unsteady gait due progressive distal weakness of peroneal muscles, pes cavus, depressed or absent deep tendon reflexes, and mild sensory loss. The histopathologic abnormalities involve all nerves in the body and occur predominantly in the fascicles. Although the classification system of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is constantly changing (because not all the causative genes have yet been described), the most common forms include the autosomal dominant types 1A and 2 that are related to DNA duplication of a region on chromosome 17 which codes for a peripheral myelin protein, and the X-linked type that is related to a mutation in the gene which codes for connexin 32, which is a gap-junction protein (Schenone and Mancardi 1999). The degree of electrophysiologic alterations varies widely among patients with different forms of the disease, especially in the type 1A, as a result of phenotypic differences and the action of stochastic factors or environmental modulation of disease severity (Schenone and Mancardi 1999). Nerves appear larger than normal but retain a normal fascicular echotexture (Heinemeyer and Reimers 1999; Martinoli et al. 2002). In considering the main genetic types of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, such as the autosomal dominant types 1A and 2, and the X-linked type, patients with type 1A have markedly larger fascicles than patients with the other disease subtypes. In these patients, the diameter of the fascicles and the resulting nerve area are more than twice those seen in healthy subjects and in type 2 and the X-linked type (Fig. 6c,d) (Martinoli et al. 2002). There is no correlation between the maximum fascicular size of the nerve and electrophysiologic features, such as distal latencies, velocities, and amplitude (Martinoli et al. 2002). In this specific clinical setting, US can be used to help the neurologist identify unrecognized disease in patients with nonspecific symptoms, to differentiate the 1A genetic subtype, and to provide a useful screening tool for a first selection of the individuals in an affected kindred who are to undergo genetic assessments.

Figure 6. a–d. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in a 37-year-old woman with type 1A disease. a Histologic slice of a fascicle of the sural nerve demonstrates the abnormal “onion bulb” appearance (arrow) of the Schwann cells, a peculiar finding of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Original magnification ×800. b Transverse T1-weighted MR image of the posterior ankle reveals an enlarged tibial nerve (arrows) characterized by swollen fascicles. The nerve is much larger than normal. Note the atrophic changes in the flexor hallucis longus muscle (asterisk) and the adjacent posterior tibial artery (a) and veins (v). c Short-axis 12–5MHz US image over the middle forearm reveals hypertrophy of the median nerve (open arrows) and its fascicles. d Corresponding 12–5 MHz US image of the median nerve obtained for comparison in a healthy woman at the same magnification shown in c demonstrates a smaller median nerve (open arrows) and fascicles. Note the equivalent size of the flexor carpi radialis (arrowheads) and palmaris longus (white arrow) tendons in the two images. The magnification scale is indicated on the right.

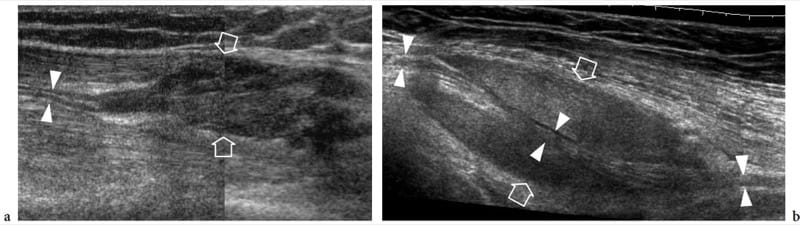

6. HEREDITARY NEUROPATHY WITH LIABILITY TO PRESSURE PALSIES

Hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies, also known as tomaculous neuropathy, is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder characterized by a tendency to develop focal neuropathies after trivial trauma that is related to a deletion in chromosome 17p11.2-12 producing reduced expression of peripheral myelin protein 22 (Verhagen et al. 1993). Histopathologically, a sausage-shaped myelin sheath swelling, the so-called tomacula, is responsible for multifocal nerve enlargement. Electrophysiologic studies demonstrate one or more entrapment neuropathies on a background of motor and sensory polyneuropathy. The more frequently involved nerves are: the peroneal nerve at the fibular tunnel, the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel, the radial nerve at the spiral groove, and the median nerve at the carpal tunnel (Verhagen et al. 1993; Beekman and Visser 2002). US is able to recognize focal nerve enlargement not only at the osteofibrous tunnels that are typically involved, but also along the course of nerves throughout the limbs (Fig. 7). It is conceivable that the “sausage-shaped” myelin swellings (tomacula) found at teased nerve fiber studies in patients with this disorder are responsible for nerve enlargement (Beekman and Visser 2002).

Figure 7. a,b. Hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies in a 42-year-old man with mild median and ulnar neuropathy. a Long-axis 12–5 MHz US image of the ulnar nerve (arrowheads) at the middle forearm with b schematic drawing correlation reveals mild fusiform thickening (arrows) of the nerve out of osteofibrous tunnels.

7. NERVE INSTABILITY

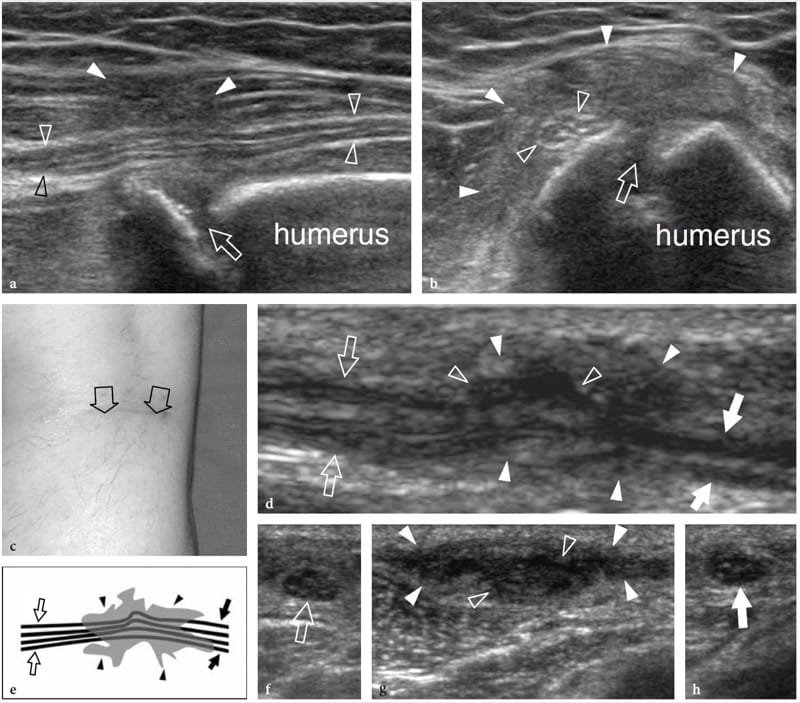

Dynamic US of the elbow can be used to help demonstrate abnormal dislocation of the ulnar nerve, with or without snapping triceps syndrome. This finding typically occurs in the cubital tunnel, an osteofibrous tunnel formed by a groove between the olecranon and the medial epicondyle and bridged by the Osborn retinaculum. Dynamic scanning during full elbow flexion can allow continual depiction of the intermittent dislocation of the ulnar nerve over the medial epicondyle if the retinaculum is loose or absent (Jacobson et al. 2001). Dislocation of the medial edge of the triceps can also occur in combination with dislocation of the ulnar nerve (Jacobson et al. 2001). In this syndrome, the ulnar nerve dislocation is secondary to the snapping triceps and dynamic scanning demonstrates the medial head of the triceps and the ulnar nerve remaining in close continuity as they dislocate over the medial epicondyle.

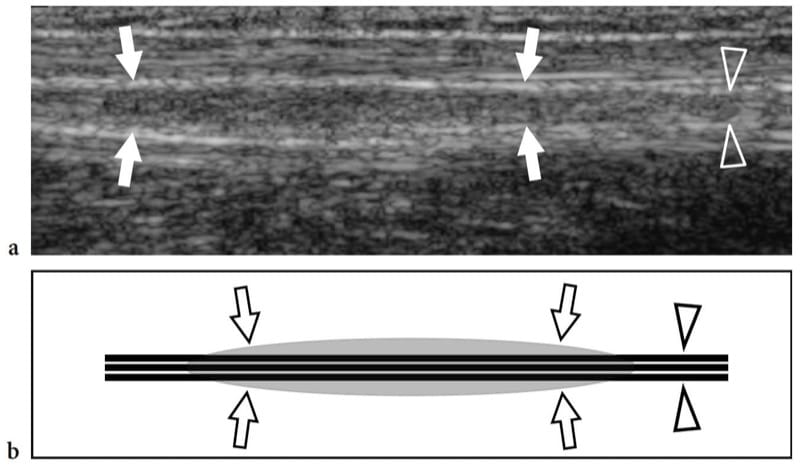

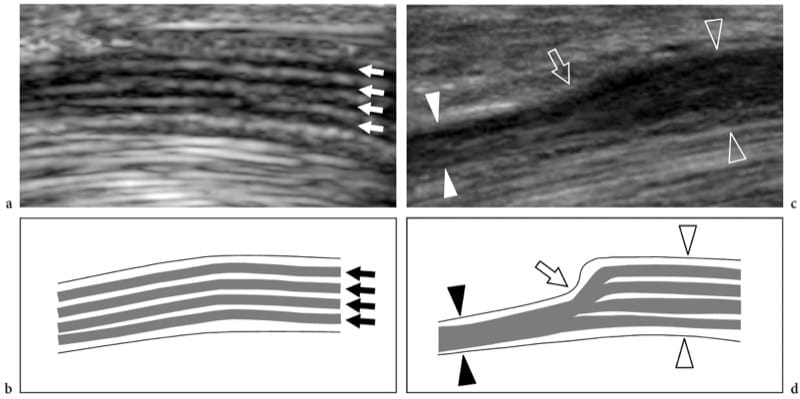

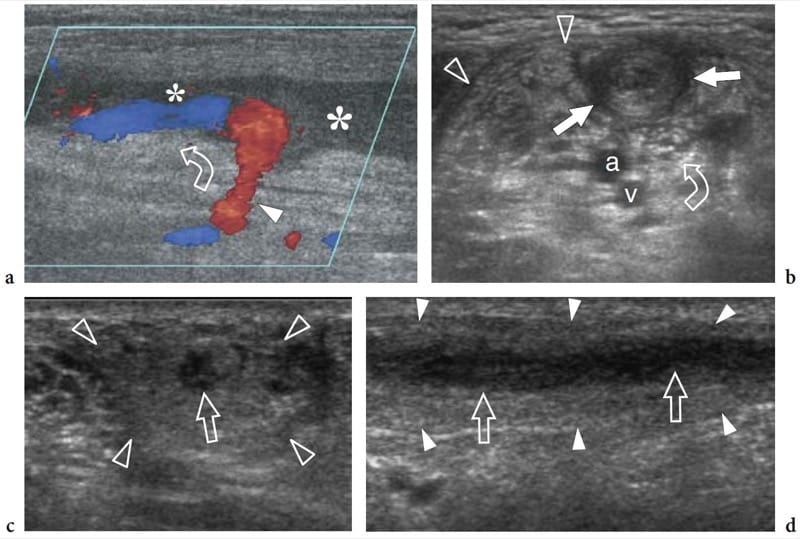

8. COMPRESSIVE SYNDROMES

From a general pathophysiologic point of view, nerve compression can occur acutely or develop chronically. Short periods of constriction result in slowing and failure of conduction across the constriction point, whereas the nerve portion distal to the region that was compressed retains a normal function. The conduction abnormalities, which are generally referred to by the term “neuroapraxia,” tend to resolve but there may be a prolonged latency until full recovery. This type of injury typically occurs in the radial nerve at the spiral groove of the humerus, the so-called “Saturday night radial palsy”, and in the peroneal nerve around the fibular head and neck, the so-called “crossed leg peroneal palsy”. If local compression is prolonged, ischemia induced by direct severe compression, mechanical distortion of the nerve architecture, may cause more significant damage in the myelin sheath and axonal degeneration (Wallerian degeneration) of the nerve fibers and persistent nerve deficit due to disruption of the axoplasm after the compression has been relieved (Delfiner 1996). In chronic nerve entrapment, irritation or compression to the nerve may induce interference with the intraneural micro-vascular supply and an ischemic reaction primarily affecting the epineurium. Venous congestion may produce endoneural edema with increased fluid pressure within the environment of the fascicles, thereby inducing a microcompartment syndrome (Shon 1994; Delfiner 1996). In the early stages, symptoms may be intermittent or even relieved after exercise, parallel to recovery of the intraneural circulation and drainage of intraneural edema. As the disease progresses, the sustained edema of the epineurium may turn into fibrotic changes with thickening and fibrosis of the nerve sheaths, further contributing to a chronic constriction of the nerve. Longstanding compression leads to damage to the myelin sheath and axonal degeneration induced by fibrosis, with permanent loss of nerve function and atrophy of the innervated muscles. Nerve trunks that are compressed chronically are typically thin at the site of compression (with reduction in the number of myelinated fibers) and swollen proximal to the compression point. The physiologic consequences related to chronic compression are slowing of conduction velocities and, occasionally, conduction block.

9. NERVE ENTRAPMENT SYNDROMES

Nerve involvement from extrinsic causes may occur anywhere in the body. However, it is more common at anatomic sites where the nerve passes in unextensible osteofibrous tunnels or beneath a prominent or abnormal band of muscle, connective tissue, or bony ridge that tethers the nerve. Diagnostic assessment of nerve compressive syndromes is essentially based on clinical features and electrophysiologic testing, and the main value of imaging is in the assessment of difficult or atypical cases, or when a mass is suspected on clinical grounds. In recent years, US has increasingly been proposed as an efficient and low-cost alternative to MR imaging for detection of compressive lesions.

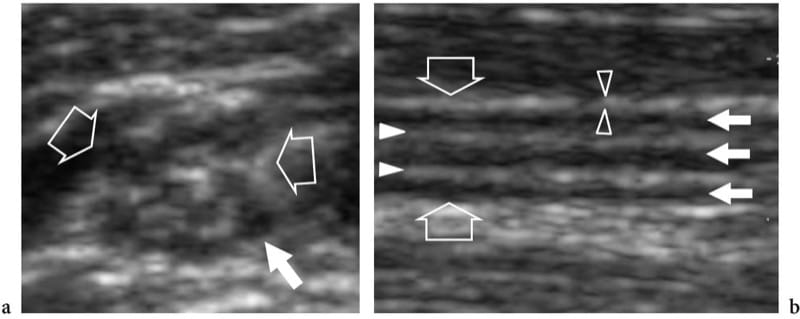

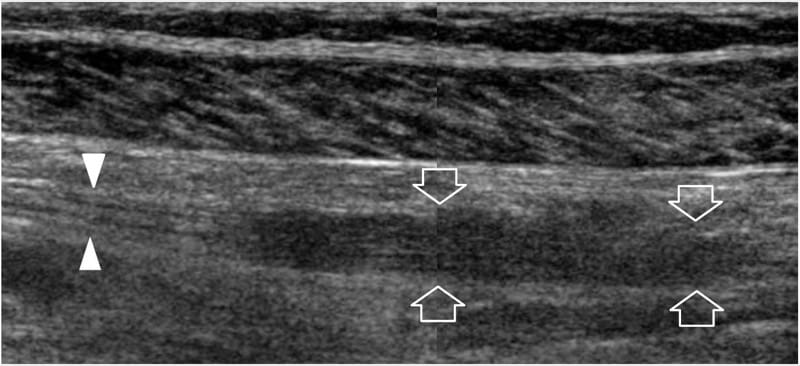

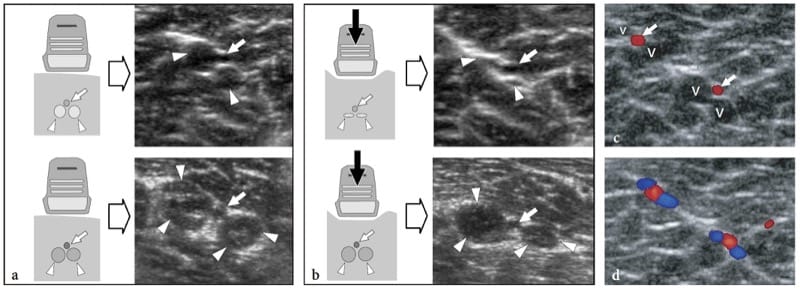

In nerve entrapment syndromes, US can demonstrate changes in both nerve shape and echotexture, the most common being a sudden flattening (notch sign) with focal reduction in the nerve cross-sectional area at the compression point and nerve swelling that occur proximal to the level of compression (Fig. 8) (Buchberger et al. 1991; Martinoli et al. 2000b). The nerve swelling is typically fusiform, extending 2–4 cm in length, and appears maximal in close proximity to the compression level, where the nerve abruptly flattens. Given these features, US is an accurate means of identifying the level of compression as located just ahead of the swollen nerve portion. Although nerve flattening should be regarded as the main sign of nerve compression, quantitative analysis of nerve thickening by means of the ellipse formula [(maximum AP diameter) × (maximum LL diameter) × (π/4)] has proved to be the most consistent criterion for the diagnosis at various entrapment sites (Chiou et al. 1998; Duncan et al. 1999; Bargfrede et al. 1999). As an ancillary finding, dynamic scanning may show a reduced mobility of the nerve over the mass or beneath the retinaculum, but this latter sign is too subjective and hard to quantify with US (Nakamichi and Tachibana 1995). At least at the carpal tunnel level, the cross-sectional area of the median nerve has also been regarded as an index for selecting patients with severe disease for which surgical decompression is indicated (Lee et al. 1999). It is conceivable that loss of axons may be associated with nerve enlargement as an expression of an increased amount of endoneural edema (Beekman et al. 2004b). In entrapment neuropathies, the nerve echotexture may become uniformly hypoechoic with loss of the fascicular pattern at the level of the compression site and proximal to it (Fig. 9). In general, the hypoechoic changes occur gradually and become more severe as the nerve nears the site of compression (Martinoli et al. 2000b). They derive from swelling of the individual fascicles and decreased echogenicity of the epineurium. The outer lining of the nerve, which is normally undefined and part of a continuum with the epineurium and surrounding fat, becomes sharp and well delineated. Depiction of such changes may increase confidence in the diagnosis and in determining the exact level of the lesion. In cases of entrapment by scar tissue, diagnostic difficulties may arise in distinguishing echotextural changes related to the compressed nerve from the scar itself, because of a similar hypoechoic appearance. Then, an enhanced depiction of intraneural blood flow signals can be appreciated with color and power Doppler techniques as a sign of local disturbances in the nerve microvasculature that occur in a compressive context (Martinoli et al. 2000b). The hypervascular pattern is more clearly appreciated in swollen hypoechoic nerves of patients with chronic, longstanding disease. Intranervous flow signals are made up of many vessel pedicles that enter the nerve from the superficial epineurium to run perpendicular to the fascicles (Fig. 10) (Martinoli et al. 1999, 2000b).

Figure 8. a–d. Entrapment neuropathies: nerve shape changes. a Long-axis 15–7 MHz US image of the median nerve at the carpal tunnel level with b schematic drawing correlation in a healthy volunteer demonstrates a normal-sized nerve and clear delineation of the fascicular arrangement (arrows). c Corresponding long-axis 17–5 MHz US image of the median nerve in a patient with severe median neuropathy reveals an abrupt change (arrow) in the size of the nerve at the proximal edge of the retinaculum (compression point). The nerve is flattened (white arrowheads) within the carpal tunnel and markedly swollen (open arrowheads) proximal to the level of compression.

Figure 9. a–d. Entrapment neuropathies: echotextural changes. a,b Short-axis 17–5 MHz US images of the right median nerve obtained a at the distal radius and b just ahead of the compression point in a patient with longstanding carpal tunnel syndrome. As the nerve (arrows) approaches the site of compression, increasing hypoechoic changes are detected due to crowding of edematous fascicles and reduced echogenicity of the epineurium. This leads to a complete loss of the fascicular echotexture. c,d Schematic drawing correlation.

Figure 10. a–d. Entrapment neuropathies: microvascular changes. a Schematic drawing illustrates the nerve vascular system, made up of perineural vessels (1) coursing alongside the nerve. These vessels give off intraneural branches that pierce the outer epineurium (2) and distribute longitudinally (3) among the fascicles. b,c Long-axis 12–5 MHz color Doppler US images of the median nerve (asterisks) in a 56-year-old patient with carpal tunnel syndrome demonstrate subtle flow signals from the longitudinal perineural plexus (arrows) and a series of intranervous branches (arrowheads) running among the fascicles. d Corresponding transverse Gd-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image obtained just deep to the flexor retinaculum (arrowheads) reveals marked uptake of contrast material in the median nerve (arrow).

Based on the US assessment, nerve entrapment syndromes can be divided into three main classes. The first includes large nerves (i.e., the median, the ulnar, the radial, the sciatic, the tibial, etc.) which are easily depicted with US at the site of compression. In these cases, US evaluation can be effectively performed with conventional (mid-range) equipment and the diagnosis is based on pattern recognition analysis and quantitative measurements. The second includes small nerves (i.e., the posterior and anterior interosseous, the musculocutaneous, the peroneal, the sural, the plantars, etc.) the depiction of which requires high-end equipment and high-performance transducers. In these cases, quantitative measurements are usually not applied. The third class includes nerves which are not detectable with US because they are either too small (i.e., most part of the saphenous, etc.), or have too deep a course and are hidden by intervening bone (i.e., the suprascapular nerve, the intrapelvic course of the sciatic and the femoral nerve, etc.). In these cases, the US diagnosis is based only on the indirect evaluation of the innervated muscles to identify denervation signs. In the first two classes, there are many sites of nerve entrapment that are amenable to US examination in the upper and lower limb, and whatever the site and the nerve involved, the US signs described previously are virtually pathognomonic of compressive neuropathy. They include: the spinoglenoid-supraspinous notch area in the posterior shoulder for the suprascapular nerve (Martinoli et al. 2003); the quadrilateral space for the axillary nerve (Martinoli et al. 2003; the spiral groove of the humerus for the radial nerve (Peer et al. 2001; Bodner et al. 1999, 2001; Rossey-Marec et al. 2004; Martinoli et al. 2004); the supinator area at the elbow for the posterior interosseous nerve (Bodner et al. 2002b; Chien et al. 2003; Martinoli et al. 2004) and the wrist for the superficial branch of the radial nerve; the cubital and Guyon tunnels for the ulnar nerve (Chiou et al. 1998; Puig et al. 1999; Okamoto et al. 2000; Martinoli et al. 2000b, 2004; Nakamichi et al. 2000; Bianchi et al. 2004; Beekman et al. 2004a; Beekman and Visser 2004); the middle forearm for the anterior interosseous nerve (Hide et al. 1999) and the carpal tunnel for the median nerve (Altinok et al. 2004; Buchberger et al. 1991, 1992; Nakamichi and Tachibana 1995; Bertolotto et al. 1996; Lee et al. 1999; Chen et al. 1997; Duncan et al. 1999; Martinoli et al. 2002b; Kele et al. 2003; Bianchi et al. 2004; El Miedany et al. 2004; Yesildag et al. 2004; Wilson 2004; Wong et al. 2004; Kotevoglu and Gülbahce-Saglam 2005; Koyuncuoglu et al. 2005; Ziswiler et al. 2005); the posterior hip or proximal thigh for the sciatic nerve (Graif et al. 1991); the fibular head and neck for the common peroneal nerve (Martinoli et al. 2000b); the tarsal tunnel for the tibial nerve (Martinoli et al. 2000b) and the inter-metatarsal spaces for the interdigital nerves (Redd et al. 1989; Read et al. 1999; Sobiesk et al. 1997; Quinn et al. 2001). A detailed overview of these syndromes is reported later in the chapters on the individual anatomic sites.

With respect to the electrophysiologic findings, a positive correlation between the nerve cross-sectional area and the severity of electromyographic findings has been found, whereas only a modest negative correlation seems to exist between electrodiagnostic parameters, such as motor velocity, CMAP amplitude, distal SNAP, and the nerve cross-sectional area (Kele et al. 2003; Beekman et al. 2004; El Miedany et al. 2004; Ziswiler et al. 2005). Generally speaking, US can complement nerve conduction studies in the evaluation of nerve entrapment syndromes. It can be informative in patients with absent motor or sensory responses, when it is difficult to localize the site of compression. A positive US study can reduce the uncertainty of nerve conduction studies and, therefore, reduces the need for further exclusionary studies. In addition, US can identify abnormal findings in the nerve surroundings, such as synovitis, space-occupying masses, or anomalous muscles, providing important information in the preoperative setting.

After surgical decompression, the US appearance and mobility of the affected nerves may improve, and it is possible to visualize the altered morphology of the osteofibrous tunnel after release of the retinaculum (Martinoli et al. 2000b; El-Karabaty et al. 2005).

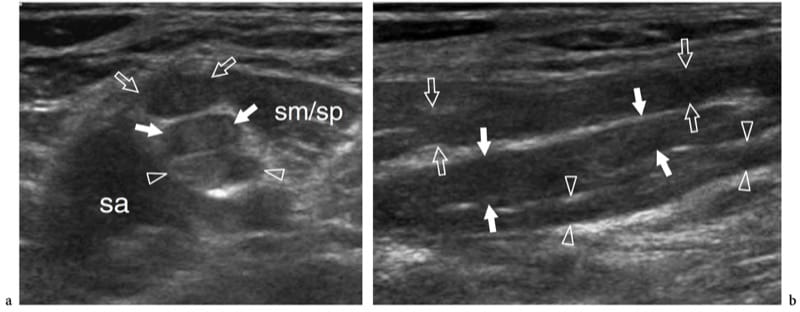

10. STRETCHING INJURIES

Nerve stretching injuries typically occur as a result of repetitive sprain or strain lesions, as well as with over-use. A characteristic injury is the avulsion of the nerve roots that occurs in brachial plexus trauma during motor vehicle accidents (Shafighi et al. 2003; Graif et al. 2004). Another typical site of nerve traction is the popliteal fossa, where the peroneal nerve may be stretched during high-grade sprains, knee dislocation or fractures (Gruber et al. 2005). In complete nerve lacerations, US reveals disruption of the fascicles with retraction and a wavy course of the nerve ends (Shafighi et al. 2003; Graif et al. 2004; Gruber et al. 2005). The outer nerve sheath may be intact. If traction injury causes partial nerve tear, a spindle neuroma (traction neuroma) can develop as an irregular swelling of hypoechoic tissue along the course of the severed nerve without evidence of nerve discontinuity (Fig. 11) (Bodner et al. 2001; Graif et al. 2004). In mild cases, the neuroma may involve only one or a few fascicles while the cross-sectional area of the nerve appears fairly normal or slightly enlarged.

Figure 11. a,b. Stretching injury (burner/stinger syndrome) of the brachial plexus nerves in a 25-year-old rugby player with persistent tingling radiating from the left shoulder to the hand and progressive weakness of the limb muscles after a significant contact injury. a Short-axis and b long-axis 12–5 MHz US images over the interscalene area demonstrate segmental thickening of the C5 (open arrows), C6 (white arrows), and C7 (arrowheads) components of the plexus (upper and middle trunks), reflecting fusiform neuromas related to stretching trauma. sa, scalenus anterior; sm/sp, scalenus medius/scalenus posterior muscles. In the burner/stinger syndrome, MR imaging of the cervical spine should always be performed to rule out nerve damage inside the spinal canal as well as herniated disks, ligament injuries, facet injuries, and undisplaced fractures.

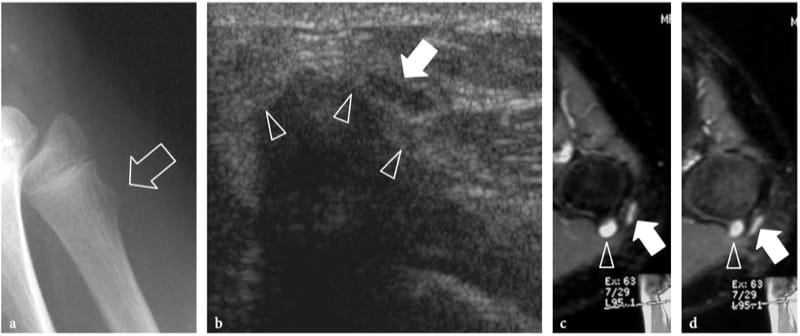

11. CONTUSION TRAUMA

Contusion trauma most often occurs where nerves run closely apposed to bony surfaces at sites of low mobility and, are therefore, more vulnerable to external injuries. In most cases, such trauma is self-resolving and does not cause morphologic changes detectable with US (Fig. 12). Repeated minor contusion trauma is usually required to cause abnormalities within the nerve substance that can be detected with US. A typical contusion trauma is that involving the radial nerve where it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum, or the deep peroneal nerve against the midfoot bones in soccer players who receive repeated blows over the dorsum of the foot (Schon 1994; Quinn et al. 2001). These lesions lead to development of a segmental fusiform thickening of the nerve at the site of trauma. A peculiar kind of contusion trauma is that involving unstable ulnar nerves at the cubital tunnel in patients with absence of the Osborne retinaculum. In predisposed subjects, the repeated friction of the nerve against the epicondyle during elbow flexion may cause chronic damage and functional deficit, so-called “friction neuritis”. In these cases, the nerve appears swollen and hypoechoic as a result of fibrotic changes and shows a thickened external epineurium (Jacobson et al. 2001).

Figure 12. a–d. Nerve contusion trauma. Peroneal neuropathy in a 15-year-old boy with onset of foot-drop after receiving a blow on the lateral knee. a Lateral plain film demonstrates an exostosis (arrow) at the fibular metaphysis. b Transverse 12–5 MHz US image reveals impingement of the peroneal nerve (arrow) against the cartilaginous component (arrowheads) of the exostosis. The nerve is swollen and hypoechoic. c,d Correlative transverse fat-suppressed GRE T2* MR images demonstrate a hyperintense nerve (arrow) crossing the exostosis (arrowhead). Note the T2-hyerintense cap of the exostosis.

12. PENETRATING WOUNDS

In penetrating wounds (glass fragments are often involved!), there may be a partial or complete interruption of the nerve fascicles. Regenerating Schwann cells and axons grow randomly at the lesion site in an attempt to restore the continuity of the nerve. Generally, the gap between the separated fascicles is wide, and new axonal sprouts develop in many directions. A hypoechoic fibrous mass is the result of such a disorganized repair process. In complete tears, stump neuromas (terminal neuromas) appear as small hypoechoic masses in continuity with the opposite edges of the severed nerve (Provost et al. 1997; Graif et al. 1991; Simonetti et al. 1999). Usually, their size is slightly larger than the axial diameter of the nerve. Most have well-defined margins; however, when they are attached to the surrounding tissues by adhesions and encasing scar tissue, their borders may be irregular or poorly defined (Bodner et al. 2001). US depiction of terminal neuromas may map the location of the nerve ends, which may be displaced and retracted from the site of the injury (Fig. 13a–c). When the nerve ends are close together, the bulk of neuroma may encase them mimicking a partial tear. In some way, this seems to suggest that US is unable to quantify the grade of nerve damage within a spindle neuroma. When the nerve is partially torn, the hypoechoic neuroma may encase resected and preserved fascicles giving rise to a homogeneous fusiform swelling of the nerve or can be seen arising specifically from the resected fascicles, while the unaffected fascicles can be appreciated continuing their course alongside the fibrous mass (Fig.14). In this latter instance, US is able to estimate the amount (percentage) of fascicles involved in the neuroma (Fig. 14d). Overall, US may help the clinical examination and nerve conduction studies to provide information about the condition of the injured nerve, and especially in deciding whether early surgical treatment is required. This is particularly true for minor nerve lesions without axonal damage.

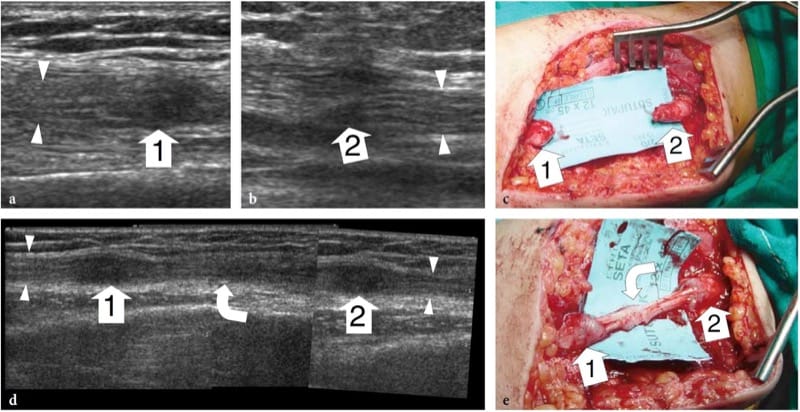

Figure 13. a–e. Complete nerve tear in a 12-year-old girl with loss of function of the median nerve after receiving a penetrating injury to the arm by a glass fragment. In the acute setting, the patient was operated on for laceration of the brachial artery. a,b Long-axis 15-7 MHz US images at the level of injury demonstrate discontinuity of the median nerve. Note the proximal and distal stumps (arrowheads) of the severed nerve ending in a hypoechoic terminal neuroma (1, 2). c Gross surgical view shows discrete retraction (4 cm gap) of the nerve ends. d After reconstructive surgery, a long-axis 12–5 MHz US image demonstrates the sural nerve graft (curved arrow) interposed between the nerve ends (arrowheads). A fusiform hypoechoic thickening is observed at the proximal (1) and distal (2) site of anastomosis: it should be regarded as a normal finding. A split-screen image was used, with the two screens aligned for an extended field of view. e Surgical correlation.

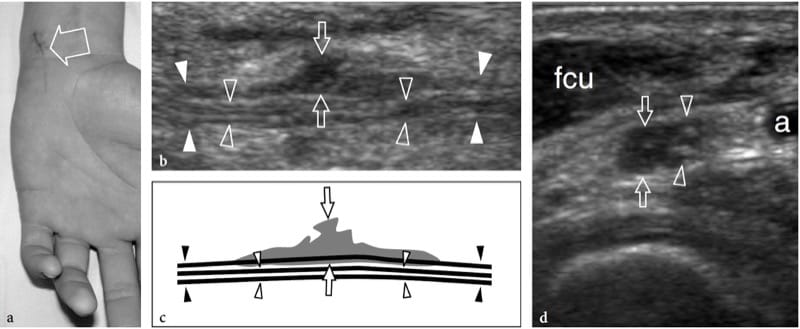

Figure 14. a–d. Partial-thickness tear of the ulnar nerve at wrist in a 15-year-old boy. The wound was produced by a sharp object and resulted in a selective motor deficit. a Photograph shows the site of injury (arrow). Observe the semiflexion deformity of the ring and little fingers related to weakness of ulnar-innervated interosseous muscles. b Long-axis 15–7 MHz US image over the main trunk of the ulnar nerve (white arrowheads in b, black arrowheads in c) with c schematic drawing correlation reveals hypoechoic tissue (arrows) involving part of the nerve fascicles, whereas some preserved fascicles (open arrowheads) are seen crossing the site of injury unaffected. d Short-axis 15–7 MHz US image demonstrates the affected (arrows) and preserved (arrowheads) portions of the ulnar nerve. Hypoechoic fibrous tissue is seen involving approximately 50% of the medial-sided fascicles of the nerve, those giving rise to the deep motor branch. Conversely, the normal lateral-sided fascicles will continue in the superficial sensory branch of the nerve. a, ulnar artery; fcu, flexor carpi ulnaris muscle.

13. POSTOPERATIVE FEATURES

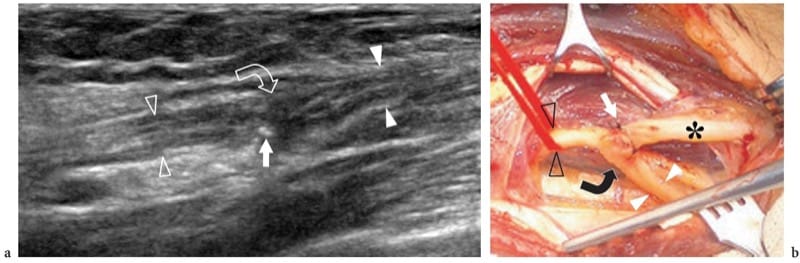

In patients with partial nerve tear, a delicate procedure of internal neurolysis of the nerve and its sheath is mainly used for either repairing the interrupted nerve fascicles or removing intraneural scar tissue. With this procedure, the main risk consists of inadvertent damage to preserved fascicles and formation of a new postoperative scar close to the nerve surface. With complete transection of the nerve, a more complex surgical procedure is required. The appropriate selection of an adequate reconstruction technique depends on the length of the gap intervening between the nerve ends after removal of irreversibly damaged tissue and terminal neuromas. Where the gap is short, an “end-to-end” anastomosis is preferred given that substantial tension on the sutured nerve stumps can be avoided. When the gap is wide, bridging with a nerve graft to obtain a “proximal nerve end–graft–distal nerve end” anastomosis is the technique of choice. For this latter procedure, tissue is usually harvested from minor superficial sensory nerves, such as the sural nerve or the medial brachial and antebrachial cutaneous nerves. Very thin sutures placed within the outer and interfascicular epineurium are used for the anastomosis. They are easily appreciated with US as bright hyperechoic spots within the nerve substance and should not be mistaken for pathologic findings, such as calcifications in granulomatous tissue (Fig. 15). In nerve reconstructive surgery, US allows a reliable postoperative evaluation of the continuity of nerve at the anastomosis, and can rule out perineural collections. A mild and fusiform increase in the nerve size at the sutures level is a normal finding. In contrast, marked irregular bulging of hypoechoic tissue at the anastomosis, possibly involving one side of the nerve, should be regarded as a pathologic sign, indicating inadequate fusion of the nerve edges and postsurgical neuroma formation (Graif et al. 1991; Peer et al. 2001). Excessive tension on the nerve edges and infection are possible causes of defective anastomosis. In this clinical setting, US may compensate for the limitations of electrodiagnosis and clinical examination by yielding reliable information on the size, extent, and localization of postsurgical scarring and neuromas with respect to further surgical intervention (Peer et al. 2003).

Figure 15. a,b. Nerve reconstructive surgery. This 62-year-old man underwent amputation of the median nerve at the forearm due to encasement by a soft-tissue sarcoma. While the proximal nerve stump was implanted in the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle, the distal stump was anastomosed with the ulnar nerve using a termino-lateral suture. After surgery, there was partial recovery of median nerve function. a Long-axis 17–5 MHz US image over the anastomosis with b correlative surgical view shows the distal stump of the median nerve (white arrowheads) sutured to the ulnar nerve (open arrowheads). Note a certain amount of spindle-shaped thickening of the nerve at the site of anastomosis (curved arrow) with some fine stitches (straight arrow) appearing as tiny hyperechoic dot-like structures at the surface of the nerve. Asterisk, ulnar nerve distal to the anastomosis.

In addition to primary (trauma-related, neurolysis-related) causes, scar formation may occur following surgery that has not been primarily directed to the nerve (i.e., fracture repair, vascular surgery, etc.). Scar tissue may encase the nerve as a whole or may lie adherent to its surface (Fig. 16). The nerve appears flattened and indistinguishable within the scar or may be distorted at its periphery with reactive focal swelling related to edema and venous congestion (Fig. 16c,h). Under these circumstances, nerve scarring may lead to persistent pain and delayed recovery of nerve function because of constant traction on the nerve and lim-ited capability for longitudinal translation during joint movements. In the postoperative setting, US findings of incidental iatrogenic injuries to peripheral nerves have been reported in the radial, femoral, accessory, and sciatic nerves (Graif et al. 1991; Peer et al. 2001; Bodner et al. 2002a; Gruber et al. 2003).

Figure 16. a–h. Postoperative encasement of nerves by scar tissue. Two different cases. a,b Radial nerve buried in a fibrous callus after repair of humeral shaft fracture. a Long-axis and b short-axis 17–5 MHz US images show focal encasement of the radial nerve (open arrowheads) by an ill-defined hypoechoic mass (white arrowheads) developing over the fracture site (arrow) reflecting the formation of fibrous callus. The nerve’s fascicular echotexture is retained within the callus. The patient underwent a second surgical look to free the nerve from the callus. c–h Peroneal nerve encased in a scar after surgical stripping of the saphenous vein. c Photograph shows the surgical access. d Long-axis 12–5 MHz US image of the peroneal nerve (arrows) with e schematic drawing correlation reveals distortion and pinching of the nerve fascicles (open arrowheads) by hypoechoic scar tissue (white arrowheads). f–h Short-axis 12–5 MHz US images obtained from f proximal to h distal show the normal peroneal nerve (open arrow) which becomes indistinguishable (open arrowheads) within the scar (white arrowheads) and then as it (white arrow) exits the scar to return to a normal appearance.

14. RHEUMATOLOGIC AND INFECTIOUS DISORDERS

In several rheumatologic disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss and Sjögren syndromes, one of the clinical landmarks of vasculitis is the appearance of neurologic findings (Lanzillo et al. 1998; Rosenbaum 2001). From the pathophysiologic point of view, vasculitis-related neuropathy affects large nerve trunks producing a multifocal degeneration of fibers as a result of necrotizing angiopathy of small nerve arteries, so-called multiple mononeuropathy (Said and Lacroix 2005). In these patients, the neuropathy does not correlate with disease parameters, such as disease activity, rheumatoid factor, and functional and radiologic scores, and there is sequential involvement of individual nerves both in time and anatomically (Nadkar et al. 2001). Nerve conduction velocities are usually not markedly reduced from normal, provided that the compound nerve or muscle action potential is not severely reduced in amplitude (Sivri and Guler-Uysal 1998). Although multiple mononeuropathy is the most common manifestation, nerve entrapment syndromes may also occur at sites where nerves pass in close proximity to either a synovial joint (i.e., cubital tunnel, tarsal tunnel, Guyon tunnel) or one or more synovial-sheathed tendons (i.e., flexor tendons at the carpal tunnel, flexor hallucis longus at the tarsal tunnel) or para-articular bursae (i.e., iliopsoas bursa at the hip). Because the clinical evaluation of nerves is often limited in these patients by simultaneous symptoms resulting from joint involvement, US imaging can contribute to distinguishing entrapment neuropathies related to derangement of joints, effusions, and synovial pannus from non-entrapment neuropathy. This is based on the fact that multiple mononeuropathy does not lead to an altered morphology of the affected nerve, whereas entrapment neuropathies do.

15. LEPROSY

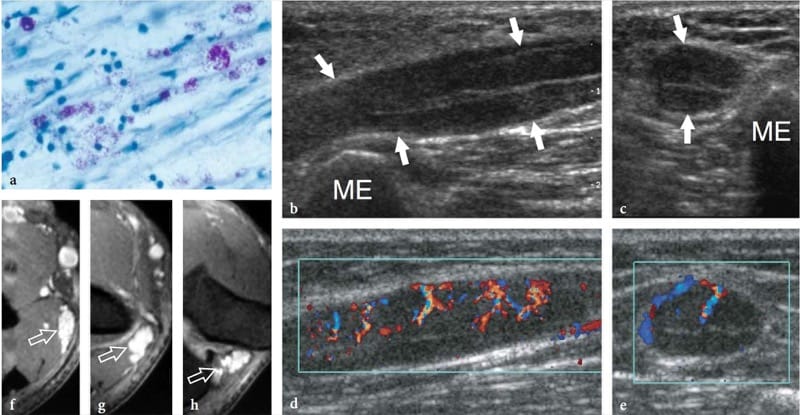

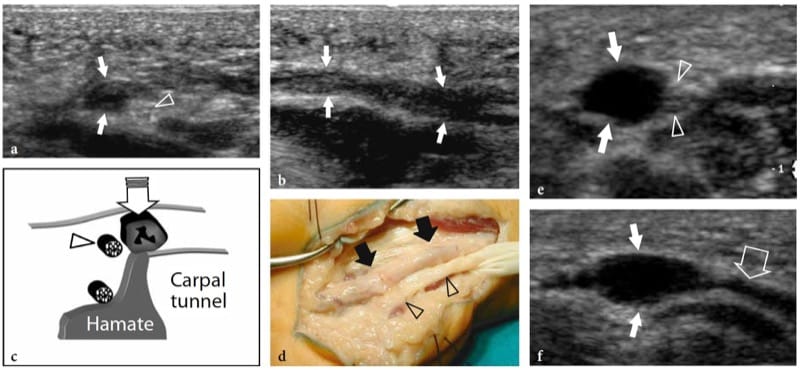

Leprosy (Hansen disease) is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae, which, in its many and various clinical forms, involves the skin and nerves (Fig. 17a). Although in the West-ern world leprosy is almost only seen in immigrants, it is endemic in developing countries (tropics and subtropics) with 12 million people affected; it therefore represents the most diffuse neuropathy in the world. Leprosy is probably spread by droplet infection, but prolonged household contact is needed and most people are not susceptible to the disease. From the clinical point of view, leprosy can be grouped into two polar forms – tuberculoid and lepromatous – between which borderline forms show an intermediate spectrum of phenotypes (Ridley and Jopling 1966). In tuberculoid leprosy, there is an intense immune response: aggressive infiltration of epithelioid and lymphoid cells into the nerve causes thickening of the epineurium and perineurium and destruction of fascicles. In the lepromatous type, the immune response is indolent and active proliferation of bacilli occurs: this form shows better preservation of the nerve architecture. Transition toward a higher resistance form of leprosy may produce episodes of acute neuritis, such as the so-called “reversal reaction” and “erythema nodosum leprosum”. During these phases, a nerve segment may become intensely painful and tender. As the disease progresses, subsequent episodes of neuritis add to the deficit until the affected nerve may be completely destroyed. Sensory abnormalities usually precede paralysis. The initial symptom of nerve involvement is sensory loss, which increases the frequency of minor trauma, leading to infections and eventually to mutilating injuries, and blindness. The preferred sites of nerve swelling in leprosy are similar to those of entrapment neuropathies (i.e., the cubital tunnel for the ulnar nerve, the carpal tunnel for the median nerve, the fibular neck for the common peroneal nerve, the tarsal tunnel for the tibial nerve). Compared with a chronically com-pressed nerve, however, the nerve enlargement is more extensive and less circumscribed. In leprosy patients, US is able to reveal nerve abnormalities including nerve swelling, hypoechoic changes in the epineurium, and loss of the fascicular echo-texture (Fig. 17b,c) (Martinoli et al. 2000c). These changes require multiple episodes of lepromatous reactions and a cumulative effect with time to become apparent at US. In fact, nerve enlargement correlates well with patients who previously underwent reversal reactions (Martinoli et al. 2000c). During the course of a reversal reaction, the affected nerve segment is markedly thickened, intensely painful and tender (Fornage and Nerot 1987; Martinoli et al. 2000c). The onset of these reactions can be indicated by an intraneural hyperemic pattern at color and power Doppler imaging (Fig. 17d-h) (Martinoli et al. 2000c). These signs suggest rapid progression of nerve damage and a poor prognosis unless antireaction treatment is started (Martinoli et al. 2000c). More rarely, “cold” soft-tissue abscesses may be seen arising from the affected nerve and spreading through the fascial planes of the limbs and extremities (Fig. 18).

Figure 17. a–h. Reversal reaction in leprosy. a Microscopic view of the sural nerve in a 25-year-old patient with leprosy reveals the presence of Mycobacteria (purple) among the nerve tissue. Ziehl-Nielsen staining; original magnification ×800. b–h Right ulnar nerve of a 22-year-old man with borderline tuberculoid leprosy examined at the elbow during the course of a reversal reaction. b Long-axis and c short-axis gray-scale 12–5 MHz US images demonstrate high-grade swelling of the nerve (arrows) with smooth fusiform enlargement of individual fascicles. ME, medial epicondyle. Corresponding d long-axis and e short-axis color Doppler 12–5 MHz US images show dramatically increased blood flow within endoneural vessels. f–h Cranial to caudal sequence of Gd-enhanced fat-suppressed MR images through the medial elbow show marked contrast enhancement into the nerve (arrow).

Figure 18. a–c. Neurogenic abscess in leprosy. a Transverse scan and b extended-field-of-view 12–5MHz US images over the tibial nerve (arrows) at the mid-distal third of the leg demonstrate a fluid collection (asterisk) arising from the nerve substance and spreading along the fascial planes, deep to the soleus muscle (So) and superficial to the tibialis posterior (tp) and the peroneals (pm). c Correlative Gd-enhanced fat-suppressed MR image shows discrete contrast enhancement in the abscess walls. Note the origin of the abscess from the nerve. Arrowhead, posterior tibial vessels. Aspiration of fluid revealed aseptic necrotic material.

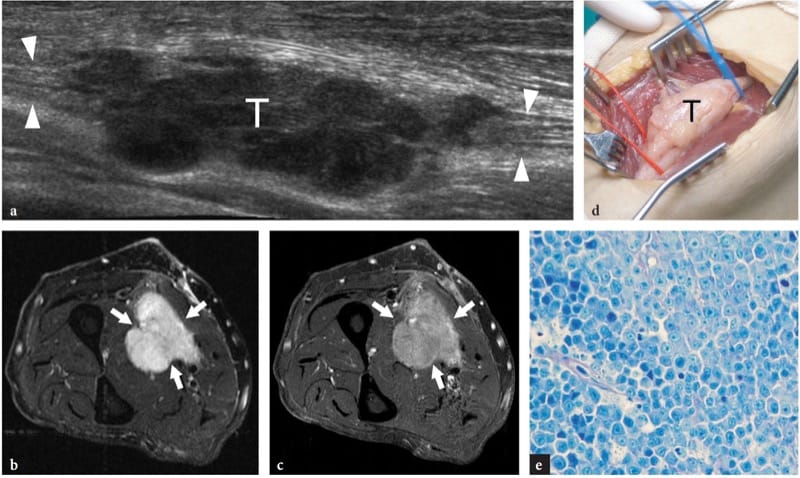

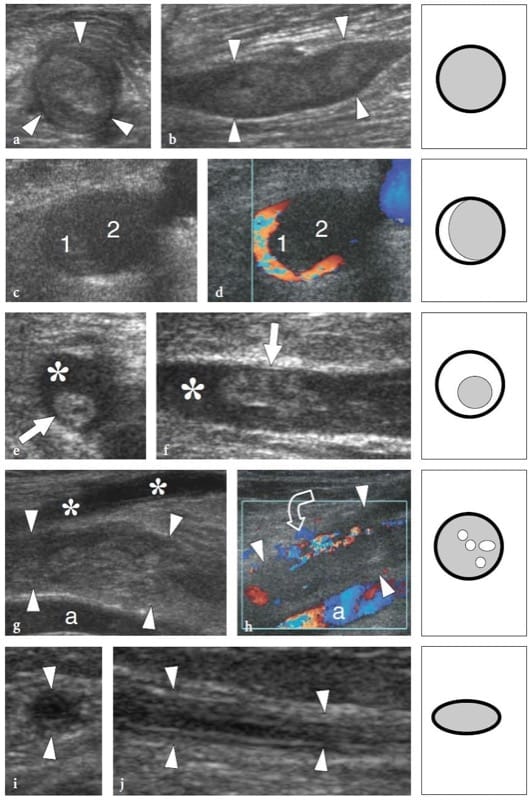

16. TUMORS AND TUMOR-LIKE CONDITIONS

Peripheral nerve tumors include two main benign forms – the schwannoma (also referred to as neurinoma or neurilemmoma) and the neurofibroma and the malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, which most often derives from the malignant (sarcomatous) transformation of a neurofibroma (Murphey et al. 1999). In addition, other masses, such as hemangiomas, lymphomas, and ganglion cysts, may occasionally develop within the nerve dissecting the fascicles and expanding inside the neural tissue. The occurrence of these masses is rare but they may cause nerve dysfunction and local symptoms and should not be mistaken for the more common nerve sheath tumors. Finally, a variety of extrinsic soft-tissue neoplasms, both benign with aggressive behavior and malignant, may involve a nerve during their local spread.

17. PERIPHERAL NERVE SHEATH TUMORS

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors derive from Schwann cells. Pain and neurologic symptoms are unusual except in large tumors (Murphey et al. 1999; Reynolds et al. 2004). Generally speaking, the US diagnosis of these tumors is based on depiction of a solid hypoechoic mass in direct continuity with a nerve at its proximal and distal poles (Fornage 1988; Beggs 1999; Martinoli et al. 2000a; Lin and Martel 2001; Reynolds et al. 2004). Detection of the junction between the tumor and the nerve of origin requires careful scanning because the nerve ends may be distorted and stretched over the mass. In addition, the nerve origin of a mass arising from a small nerve (consisting of a single hypoechoic fascicle) may not be reliably assessed: this can be especially true in superficially seated lesions. Some differential features have been described among tumor histotypes, and especially between schwannomas and neurofibromas.

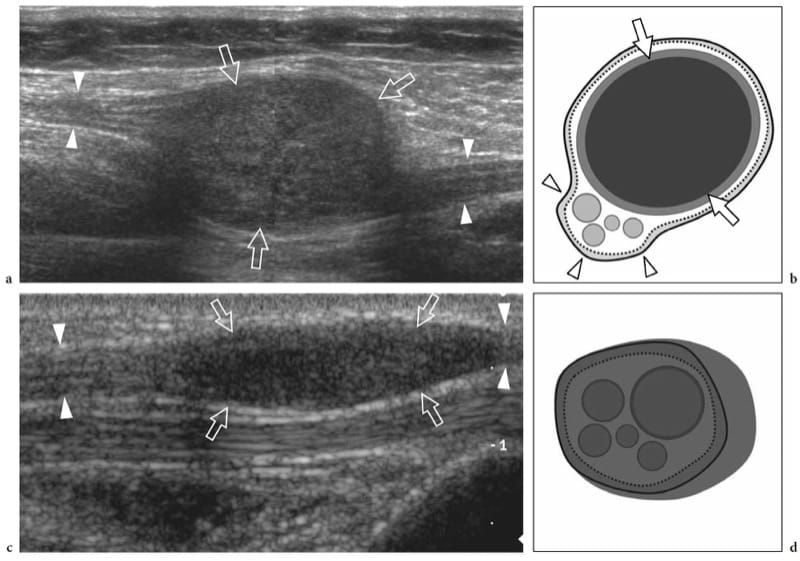

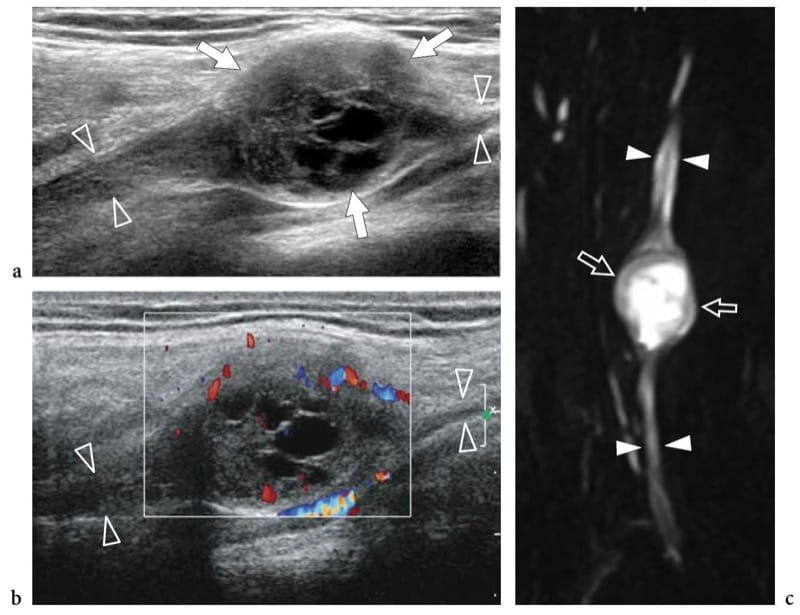

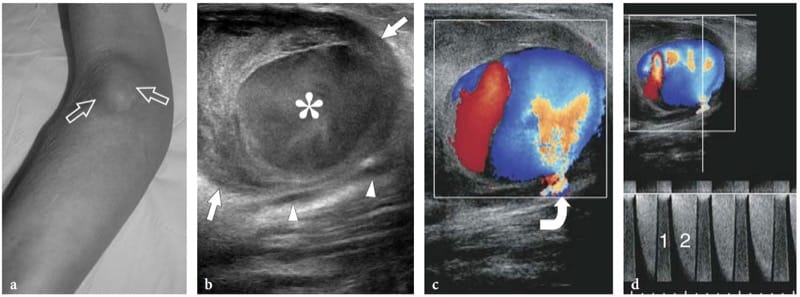

Schwannomas are slowly growing encapsulated tumors that are found more commonly in the extremities. They are composed of neoplastic cells that have the ultrastructural characteristics and antigenic phenotype of Schwann cells but do not contain axons (Woodruff 1993). Most appear as solitary globoid masses located along a nerve and eccentric to the nerve axis, with homogeneously hypoechoic echotexture, posterior acoustic enhancement, and a hypervascular pattern at color and power Doppler imaging (Fig. 19a,b) (Fornage 1988; Beggs 1999; Martinoli et al. 2000a; Lin and Martel 2001; Reynolds et al. 2004). Occasionally, intratumoral cystic changes related to accumulation of myxoid matrix (cystic schwannoma) and calcifications (ancient schwannoma) can be recognized (Fig. 20) (Isobe et al. 2004). Distinguishing cystic schwannomas from intraneural ganglia may be aided by the characteristic location of the latter (see below). In schwannomas, the proximal nerve end outside the tumor may appear thickened and hypoechoic with loss of the fascicular pattern, thus producing a tapering appearance to the oval mass. This can be appreciated even for a long nerve segment and seems, at least in part, to reflect the infiltration of tumor cells along the fascicles (Graif M., unpublished data). Such abnormalities are usually not seen in the distal end of the affected nerve. In addition, schwannomas may be seen developing from an individual fascicle, which appears diffusely thickened even at a distance from the mass, whereas the other fibers of the same nerve are displaced by the bulk of the tumor but remain unaffected with regard to size and echotexture (Fig. 21a). This can explain why some schwannomas seems to have central continuity with the long axis of the nerve.

Figure 19. a–d. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors. a,b Schwannoma of the tibial nerve at the posterior leg. a Long-axis gray-scale 12–5 MHz US image with b schematic drawing correlation depicts the tumor as a globoid hypoechoic mass (arrows) which develops eccentrically at the periphery of the nerve (arrowheads). c,d Neurofibroma of the median nerve at the distal forearm. c Long-axis gray-scale 12-5 MHz US image with d schematic drawing correlation shows the tumor as a hypoechoic spindle-shaped mass (arrows) expanding within the nerve and involving the fascicles (arrowheads). Focal enlargement of the nerve and disappearance of the fascicular pattern is observed.

Figure 20. a–c. Cystic schwannoma. a,b Long-axis a gray-scale and b color Doppler 12–5 MHz US images over the radial nerve (arrowheads) at the arm with c MR-neurographic correlation show a rounded mass (arrows) with intratumoral cystic changes, related to accumulation of myxoid matrix, in continuity with the parent nerve (arrowheads). The tumor exhibits a hypervascular pattern made up of peripheral and central color Doppler signals.

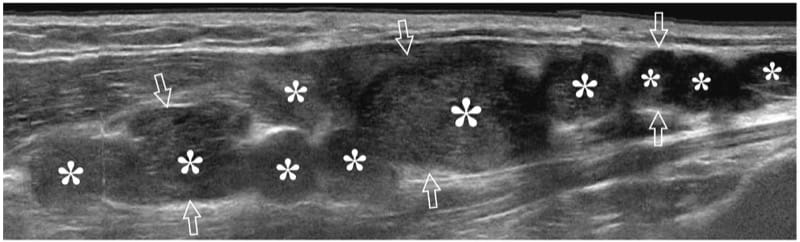

Neurofibromas, on the other hand, are intimately associated with the parent nerve, developing in a fusiform (not globoid) fashion, with the nerve entering and exiting from the extremities of the lesion (Fig. 19c,d) (King et al. 1997; Lin and Martel 2001). Histopathologically, they are composed of a mixture of cell types, the predominant one of which has characteristics of the perineurial cells. As the proliferative cells of a neurofibroma grow, they spread through the epineurium into the surrounding soft tissue. Neurofibromas can be categorized into three forms: localized, diffuse, and plexiform (associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis). The localized variety is the most common, accounting for approximately 90% of cases (Murphey et al. 1999). Often, a target sign formed by a subtle central hyperechoic region within the hypoechoic mass can be found in these tumors, reflecting a central fibrotic focus surrounded by peripheral myxomatous tissue (Fig. 21b–d) (Lin et al. 1999). Neurofibromas are less hypervascular than schwannomas at color and power Doppler imaging. Unlike localized neurofibromas, diffuse neurofibromas primarily involve the skin and the subcutaneous tissue and presents as a plaque-like elevation of the skin with thickening of the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 22a,b) (Murphey et al. 1999).

Figure 21. a–d. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors: peculiar US findings. Two different cases. a Schwannoma of the median nerve at the bicipital sulcus. Long-axis 12–5 MHz US image depicts the tumor (T) as an eccentric hypoechoic mass in continuity with the nerve (open arrowheads). At its proximal and distal ends, the tumor is connected with a swollen fascicle (asterisks), whereas the other fascicles (white arrowheads) remain unaffected and displaced at the periphery of the mass. A split-screen image was used, with the two screens aligned for an extended field of view. b–d Neurofibroma. b Long-axis and c short-axis 12–5 MHz US images of a small neurofibroma in the thigh with d fat-suppressed T2-weighted MR imaging correlation reveal a well-delineated oval mass (arrows) in continuity with the posterior femorocutaneous nerve (arrowheads). The tumor is characterized by concentric hypoechoic and hyperechoic layers (1, 2, 3) consistent with the sonographic target sign.

Figure 22. a–f. Neurofibroma: spectrum of US appearances. Three different cases. a,b Diffuse neurofibroma. a Transverse 12–5 MHz US and b T1-weighted MR images of the suprapatellar region in a 10-year-old child without neurofibromatosis show an ill-defined infiltrative mass (arrowheads) extending along the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior knee. c,d Sessile neurofibroma. c Photograph of the right forearm of a 43-year-old man with neurofibromatosis shows a sessile cutaneous neurofibroma (arrow) associated with café-au-lait spots (arrowheads). d The 17–5 MHz US image demonstrates the sessile neurofibroma as a superficial solid hypoechoic mass (straight arrows) arising from the dermis (curved arrow). e–f Plexiform neurofi bromas. e Long-axis 12–5 MHz US image over the sciatic nerve in an 8-year-old child with intra- and extra-abdominal neurofibromatosis demonstrates multiple neurofibromas (asterisks) arising from individual fascicles of the sciatic nerve (arrows). f Coronal T2-weighted MR image of the pelvis and the proximal thigh shows innumerable neurofibromas along the course of a thickened and hyperintense sciatic nerve (arrows).

As regards the malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, the only findings which may make the examiner suspect that a nerve tumor is malignant are a sudden increase in size of a previously stable nodule and the presence of indistinct margins and adhesions of the mass with surrounding tissues. Especially in patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis, a rapidly enlarging nodule indicates the need for immediate biopsy.

Despite these differences, US cannot distinguish among schwannoma, neurofibroma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (Lin and Martel 2001; Reynolds et al. 2004). US can contribute to the preoperative assessment of the extent of disease, by defining the relationship of the tumor to adjacent neurovascular structures and surrounding muscles and also by assisting surgical planning. After imaging assessment, fine needle aspiration biopsy of the mass can be confidently performed under US guidance. During biopsy, excruciating pain is frequently triggered by the needle insertion. From the surgical point of view, schwannomas may be shelled out preserving nerve continuity and function (Murphey et al. 1999). In the postoperative setting, residual hypoechoic thickening of the nerve at the site of tumor resection is almost invariably seen with US: this should be regarded as a normal finding (Fig. 23). Recurrence is unusual. In contrast, surgical resection of neurofibromas requires sacrificing the parent nerve because the mass cannot be separated from the nerve fascicles, and subsequent nerve grafting is needed to preserve and restore function. Although surgical management may be acceptable in cutaneous neurofibromas, deep-seated lesions are usually managed conservatively to avoid functional deficit.

Figure 23. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors: postsurgical findings. Long-axis 12–5MHz US image over the tibial nerve (arrowheads) at the mid-posterior leg in a 48-year-old woman who was previously operated on for schwannoma shows residual hypoechoic thickening (arrows) of the nerve at the site of tumor resection with loss of the fascicular echotexture. This finding was stable at 3 year follow-up. A split-screen image was used, with the two screens aligned for an extended field of view.

Type 1 neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen disease), a relatively common (1:2500–3000 births) inherited autosomal dominant disease related to an alteration of a gene on chromosome-17, presents with the typical clinical triad of cutaneous lesions (café-au-lait spots), skeletal deformities (scoliosis), and mental deficiency. Widespread involvement by neurofibromas of the localized, diffuse, and plexiform variety occurs with tumors arising from small dermal nerves and large deep-seated nerves. In neurofibromatosis, localized neurofibromas often involve the dermis and the subcutaneous tissue: when pedunculated, they are referred to as the “fibroma molluscum” (Fig. 22c,d) (Murphey et al. 1999). In plexiform (multinodular) neurofibromatosis – the pathognomonic form of the disease – innumerable neurofibromas are generated from the fascicles of a large nerve trunk, which is typically involved for a long segment together with its branches, leading to the so-called “bag-of-worms” appearance of the affected nerve at gross inspection and US imaging that results from the diffuse tortuous nerve thickening (Figs. 22e,f, 24) (Murphey et al. 1999). A disfiguring giant enlargement of the extremities may be associated, so-called elephantiasis neuromatosa (Murphey et al. 1999). Plexiform neurofibromas are indistinguishable from the more rare plexiform schwannomas which sporadically occur in children and young adults: the latter are not associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis and do not undergo malignant transformation (Fig. 25) (Ikushima et al. 1999; Katsumi et al. 2003).

Figure 24. Plexiform neurofibromatosis. Long-axis extended-field-of-view 17–5 MHz US image over the median nerve (arrows) at the forearm in a patient with neurofibromatosis shows multiple plexiform neurofibromas (asterisks), some of which have a central hyperechoic area representing the target sign. The median nerve is markedly enlarged and shows a convoluted multinodular appearance.

Figure 25. a–d. Plexiform schwannoma. a Photograph of the right hand of a 4-year-old child with an elongated palpable lump ( arrows) on the palm, growing in between the third and fourth metacarpals. b Extended-field-of-view 17–5 MHz US image oriented along the long axis of the lump with fat-suppressed c T2-weighted and d postcontrast GRE T1-weighted MR imaging correlation demonstrates a multinodular hypoechoic mass (arrows) made up of swollen convoluted fascicles arising from the median nerve (arrowheads) and branching distally. The tumor appears hyperintense in T2 and after gadolinium administration.

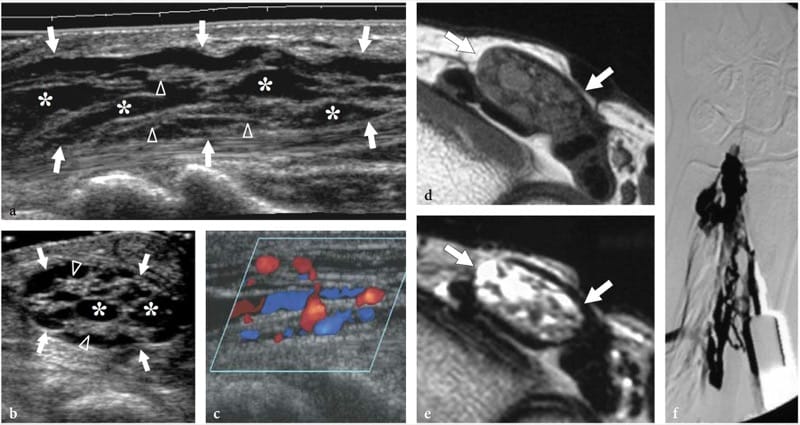

18. HEMANGIOMA AND NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMA

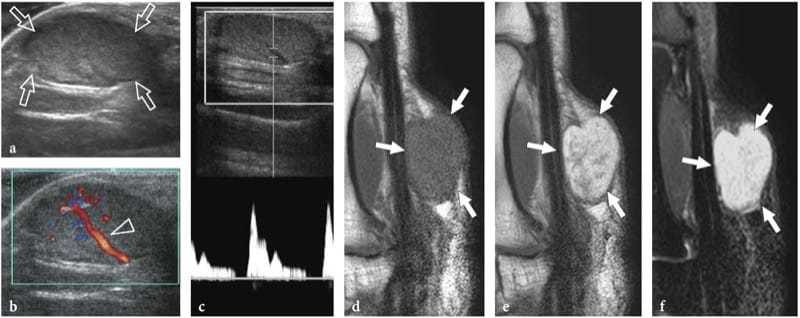

Nerve hemangiomas are extremely rare tumors arising from the endothelial lining of the endoneurium from which new vessels arise or infold within nerves from the perineural tissue. Most are recognized in children and young patients; there is no gender prevalence. The tumors tend to enlarge with age, or because of stimulating factors such as and trauma (Bilge et al. 1989). Nerve hemangiomas have a predilection for the median nerve; a persistent median artery has been advocated to explain this prevalence (Prosser and Burke 1987). Clinical findings include palpable nerve swelling at the distal forearm with or without symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. US reveals a markedly swollen median nerve containing large intraneural fluid-filled spaces separating the fascicles (Fig. 26). Typically, these anechoic spaces are oriented according to the long-axis of the nerve and compressible with the transducer. Color and power Doppler imaging show slow-flowing blood within them (Fig. 26c). Venous waveforms are predominant at spectral Doppler analysis. Surgical neurolysis of nerve hemangiomas is not recommended because intraneural vessels are part of the “vasa nervorum” system and due to the intermingled distribution of vessels with fascicles. In symptomatic patients, carpal tunnel release may be performed to improve the clinical symptoms.

Primary non-Hodgkin lymphomas affecting peripheral nerves are very rare. Most involve the sciatic nerve and are the result of direct spread from adjacent tumors (Roncaroli et al. 1997). Peripheral neuropathy may also be appreciated in the absence of direct involvement of the nerve as a paraneoplastic manifestation of lymphoproliferative disorders. From the histopathologic point of view, the affected nerves show extensive neoplastic infiltration of the endoneurium and perineurium. The nerve fascicles are separated by diffuse infiltrates of neoplastic lymphoid cells contained within a thickened epineurium (Eusebi et al. 1990). US reveals a heterogeneous nerve mass with distortion and swelling of the individual fascicles (Fig. 27). The treatment usually consists of chemo- and radiotherapy (Pillay et al. 1988).

Figure 26. a–f. Hemangioma of the median nerve in a 40-year-old woman with carpal tunnel syndrome and a large intramuscular hemangioma extending through the flexor muscles of the forearm down to the carpal tunnel. The patient underwent release of the retinaculum and partial resection of the mass with removal of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle. a Long-axis and b short-axis 17–5 MHz US images obtained at the distal radius show an enlarged median nerve (arrows) with intranervous abnormal fluid-filled spaces (asterisks) running alongside the fascicles (arrowheads). c Longitudinal color Doppler 12–5 MHz US image reveals slow-flowing blood within the intraneural spaces indicating a hemangioma. Vessels are compressible and exhibits venous waveforms. d,e Correlative transverse d T1-weighted and e T2-weighted MR images show increased T2 signal intensity in the epineurium surrounding the fascicles of the median nerve (arrows), due to the presence of abnormal vessels within the nerve substance. f Digital subtraction angiography confirms the presence of a venous network in the median nerve.

Figure 27. a–e. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the median nerve in a 62-year-old man with a slowly growing painless soft-tissue mass at the mid-forearm. a Extended-field-of-view 17–5 MHz US image with transverse fat-suppressed b T2-weighted and c gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MR imaging correlation demonstrates a lobulated multinodular hypoechoic mass (T) in continuity with the fascicles of the median nerve (arrowheads), an appearance quite different from that of peripheral nerve sheath tumors. The tumor (arrows) appears diffusely hyperintense in T2 and after gadolinium administration. d Gross surgical view confirms the neurogenic nature of the mass (T). e Histologic specimen shows diffuse involvement of the nerve tissue by lymphoid elements. Original magnification ×800.

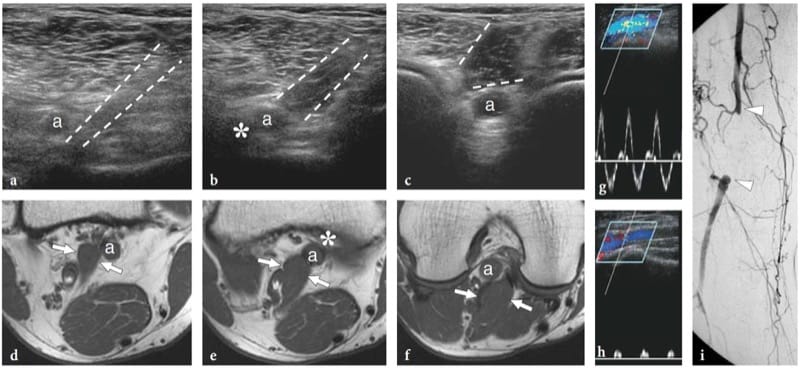

19. INTRANEURAL GANGLIA

The incidence of intraneural ganglia is relatively low, affecting most frequently the common peroneal nerve (Yamazaki et al. 1999). This nerve originates at the apex of the popliteal fossa from the sciatic nerve and moves downward to the fibular head, where it divides into its two terminal branches: the deep and the superficial peroneal nerve. Around the fibular neck, the deep peroneal nerve gives off a small recurrent articular branch to supply the capsule of the superior tibiofibular joint. The capsular ending of this small branch may lead to the development of intraneural ganglia (Spinner et al. 2003, 2005). In fact, this branch serves as a conduit for cyst fluid to pass from the joint space into the nerve (Spinner et al. 2003). The joint fluid dissects the epineurium among the fascicles and moves toward the deep peroneal nerve, the common peroneal nerve and even the sciatic nerve, forming an elongated intraneural cyst. Intraneural ganglia do not have a fibrous capsule or a synovial lining and must be differentiated from the more common extraneural ganglia. As an extension of the superior tibiofibular joint, they appear as spindle-shaped cystic masses contained within the nerve sheath that grow in the space between the epineurium and the nerve fascicles (Martinoli et al. 2000b).

20. NERVE ENCASEMENT BY EXTRINSIC NEOPLASMS

Extrinsic soft-tissue tumors may involve normal nerves by contiguity. They may either displace and compress the nerve at the periphery of the mass without infiltrative signs or can incorporate the nerve. In the first instance, the integrity of the nerve can be preserved at surgery after removal or debulking of the mass. In the latter, the surgical procedure is obliged to sacrifice the encased nerve together with the tumor (Fig. 28). US may aid in assessing the extent of tumor preoperatively, and in defining the exact relationship of the mass with the nerve and its divisional branches (Fig. 29).

Figure 28. a,b. Nerve involvement by extrinsic tumors. Two different cases. a Longitudinal 12–5 MHz US image over the lateral knee in a 25-year-old patient with relapsed desmoid tumor after surgery demonstrates the peroneal nerve (arrowheads) incorporated by the mass (arrows). b Oblique longitudinal 12-5 MHz US image over the mid-distal third of the arm in a 67-year-old woman with liposarcoma shows a long segment of the radial nerve (arrowheads) encased by the neoplasm (arrows). In both cases, surgery was obliged to sacrifice the involved nerve.

Figure 29. a,b. Nerve involvement by extrinsic tumors. a Oblique longitudinal 12-5 MHz US image over the popliteal fossa demonstrates a large lipomatous mass (asterisks) encasing the peroneal nerve (arrowheads). A split-screen image was used, with the two screens aligned for an extended field of view. b Gross surgical view shows the bifurcation of the sciatic nerve (arrow) into the tibial (open arrowheads) and the peroneal (white arrowheads) nerves. This latter nerve can be seen infolding within the mass (asterisks). Pathologic examination revealed a liposarcoma.

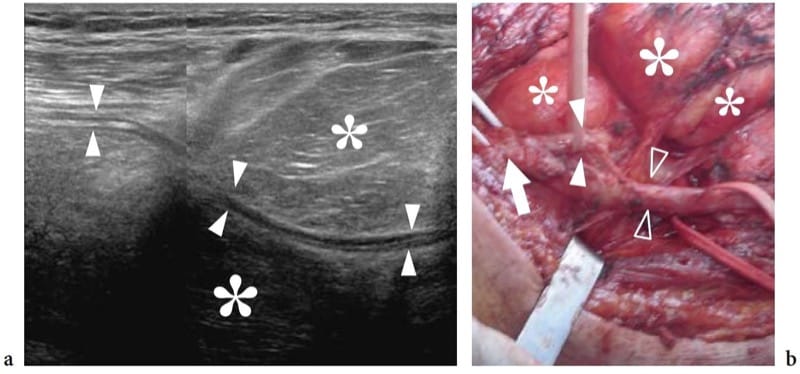

21. BLOOD VESSELS

An in-depth complete treatise on the arteries and veins running in the limbs and extremities and related-pathology is beyond the scope of a book on the musculoskeletal system. Here, we will focus on general aspects of vascular pathology related to musculoskeletal diseases. The analysis of the proper vascular pathology of limb arteries and veins, such as atherosclerotic disease and venous insufficiency, is more appropriately dealt with in other textbooks and specific literature (Polak et al. 1989; Edwards and Zierler 1992; Foley et al. 1989; Fraser and Anderson 2004).

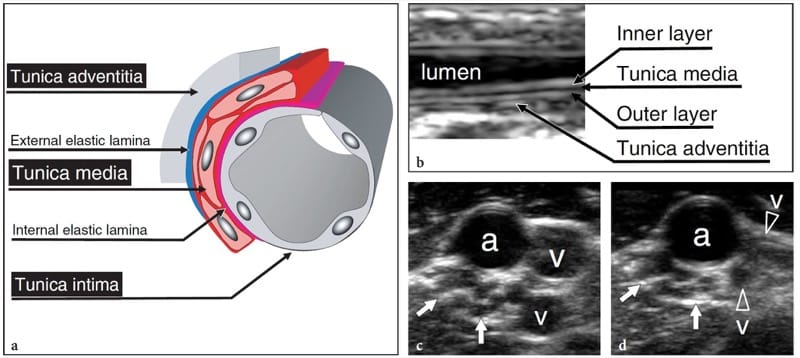

22. HISTOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS

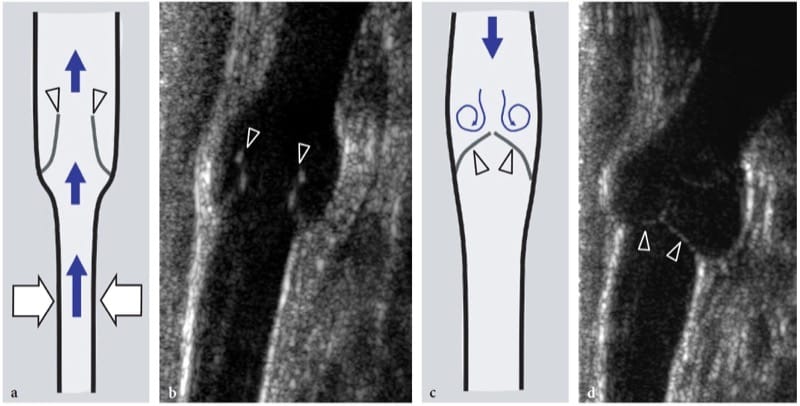

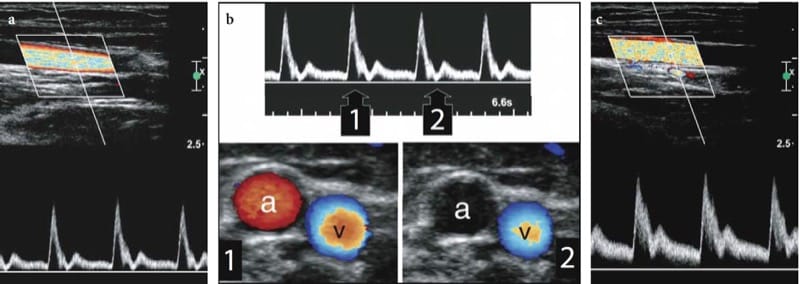

Based on their histologic architecture, the arteries can be divided into four different groups: elastic arteries, medium-sized muscular arteries, small arteries, and arterioles (i.e. the radial and ulnar arteries belong to the medium-sized muscular group). Elastic arteries are the largest in the body; they expand when the heart contracts and return to a normal caliber in diastole. Muscular arteries are small and middle-sized vessels with a relatively narrow lumen and thick walls consisting of circumferentially arranged smooth muscle fibers which restrict the lumen when they contract. The tonus of the smooth muscle component depends on the autonomic nervous system and is responsible for the round cross-sectional shape of the arteries, for blood pressure levels, and for regulatory functions of blood flow (i.e. increased flow volume in the skeletal muscles during exercise). The arterial wall is composed of three concentric layers: the intima (inner tunica) containing the endothelial lining; the media (intermediate tunica) housing smooth muscle tissue; and the adventitia (outer tunica) characterized by fibrous tissue merging with the loose connective space around the vessel (Fig. 30a). In a muscular artery, the lamina elastica interna lies between the intima and the media, whereas the lamina elastica externa separates the media from the adventitia.