Prevention, diagnosis, and management of post-dural puncture headache – Consensus practice guidelines from an international working group

Introduction

Postdural puncture headache (PDPH) is a significant complication that can occur following procedures involving the puncture of the dura mater, such as epidural analgesia or spinal anesthesia. While the incidence of PDPH varies widely—ranging from less than 2% to 40%—it poses a considerable challenge in both diagnosis and management. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the evidence-based guidelines on PDPH, focusing on prevention, diagnosis, and management strategies, as outlined in the latest multi society consensus report.

What is Postdural Puncture Headache?

PDPH typically occurs within the first five days following a dural puncture, characterized by a headache that is often postural—worsening when the patient is upright and improving when lying down. Other symptoms can include neck stiffness, auditory disturbances, and sometimes more severe complications like subdural hematoma or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. While many cases resolve within two weeks, the impact on the patient’s quality of life, particularly in postpartum patients, can be profound.

Risk factors for PDPH

- Age: Younger patients, particularly those under 40, are more likely to develop PDPH. This risk diminishes significantly in patients over 60.

- Gender: Females, especially those in the obstetric population, are at a higher risk than males.

- Body mass index (BMI): A lower BMI is associated with a higher risk of PDPH, while obesity appears to confer some protection, possibly due to increased epidural pressure reducing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage.

- History of headache: A history of headaches, particularly frequent or recent, increases the risk of PDPH.

- Smoking and depression: Limited evidence suggests that smoking might reduce the risk of PDPH, while depression has been linked to a higher incidence. However, more research is needed in these areas.

Procedural factors

- Needle type and size: Non-cutting needles (atraumatic or pencil-point) reduce the incidence of PDPH compared to cutting needles (like the Quincke needle). Narrower gauge needles also tend to decrease PDPH risk.

- Needle insertion technique: The midline approach is preferred, and orienting the bevel parallel to the spine may reduce PDPH in procedures using cutting needles.

- Multiple Attempts and Operator Experience: Repeated attempts at dural puncture and less experienced operators performing the procedure increase the risk of PDPH.

Diagnosis of PDPH

Diagnosing PDPH requires careful consideration of clinical presentation. The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3) defines PDPH as a headache attributed to low CSF pressure that occurs within five days of a lumbar puncture. However, diagnosing PDPH can be complex due to variability in symptoms and the potential for delayed onset, sometimes beyond the typical five-day window.

Management strategies

Managing PDPH involves both conservative treatments and more invasive procedures depending on the severity of symptoms:

- Conservative management

- Bed rest and hydration: These are often recommended, though evidence supporting their efficacy is limited.

- Pharmacological treatments: NSAIDs and caffeine have been used to alleviate symptoms, though their effectiveness varies.

2. Epidural Blood Patch (EBP)

- The most definitive treatment for severe PDPH, EBP, involves injecting the patient’s blood into the epidural space to seal the dural puncture. This procedure is typically reserved for cases where conservative measures fail to provide relief.

3. Prophylactic measures

- Prophylactic EBPs can be considered following an inadvertent dural puncture, although the decision should be individualized. Evidence on the effectiveness of prophylactic EBPs in preventing PDPH is mixed, and routine use is not universally recommended.

4. Follow-up and monitoring

- Patients undergoing procedures with a risk of PDPH should be monitored closely, especially within the first few days after the procedure. Regular follow-up is crucial to ensure early detection and management of symptoms.

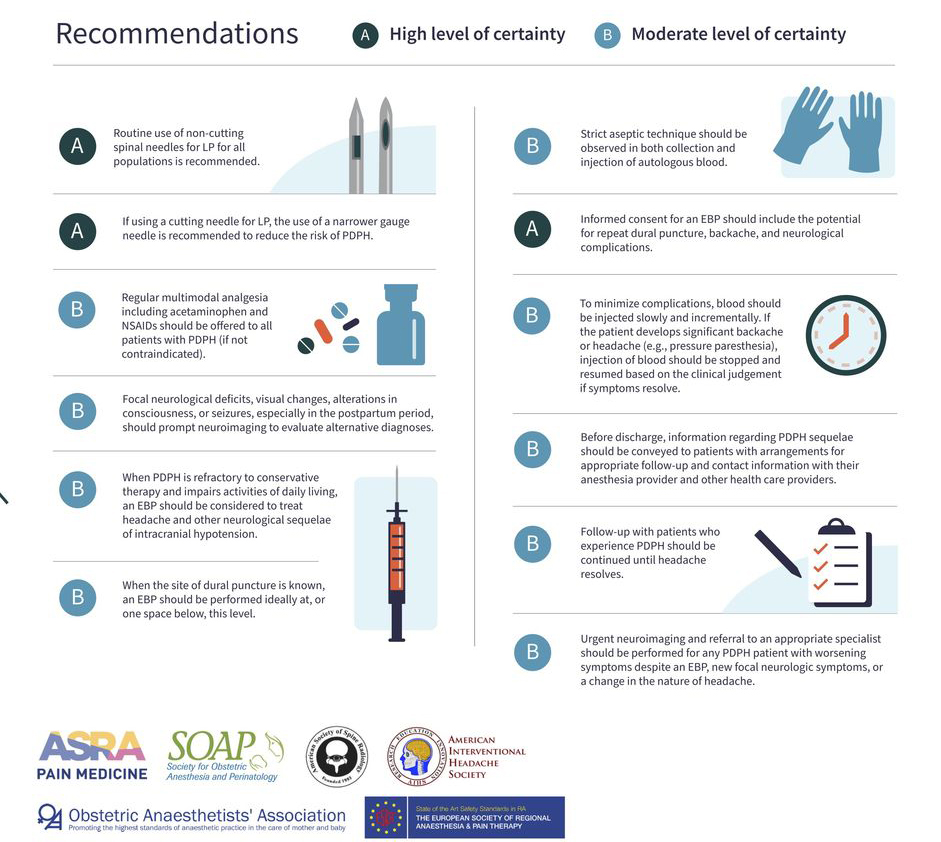

Latest recommendations

Consensus practice guidelines on postdural puncture headache from a multi-society, international working group. EBP, epidural blood patch; LP, lumbar puncture; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PDPH, postdural puncture headache. This infographic was adapted from Uppal et al. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine 2024;49:471-501.

Future directions

There remain areas of uncertainty that require further research, including the optimal techniques for needle insertion, the role of prophylactic EBPs, and the best practices for managing atypical presentations of PDPH.

Conclusion

PDPH remains a significant clinical challenge, but with careful attention to risk factors, procedural techniques, and early intervention strategies, the incidence and impact of this condition can be mitigated. Health professionals must stay informed of the latest guidelines and be prepared to implement evidence-based practices to manage this complex condition effectively.

For more detailed information, refer to the full article in Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine.

Uppal V, Russell R, Sondekoppam RV, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on postdural puncture headache: a consensus report from a multisociety international working group. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine 2024;49:471-501.

For more information on postdural puncture headache, enroll in the Regional Anesthesia Manual e-Course on the NYSORA website or explore this topic in our newest Anesthesiology Manual: Best Practices & Case Management. Don’t miss out—get your copy on Amazon or Google Books.