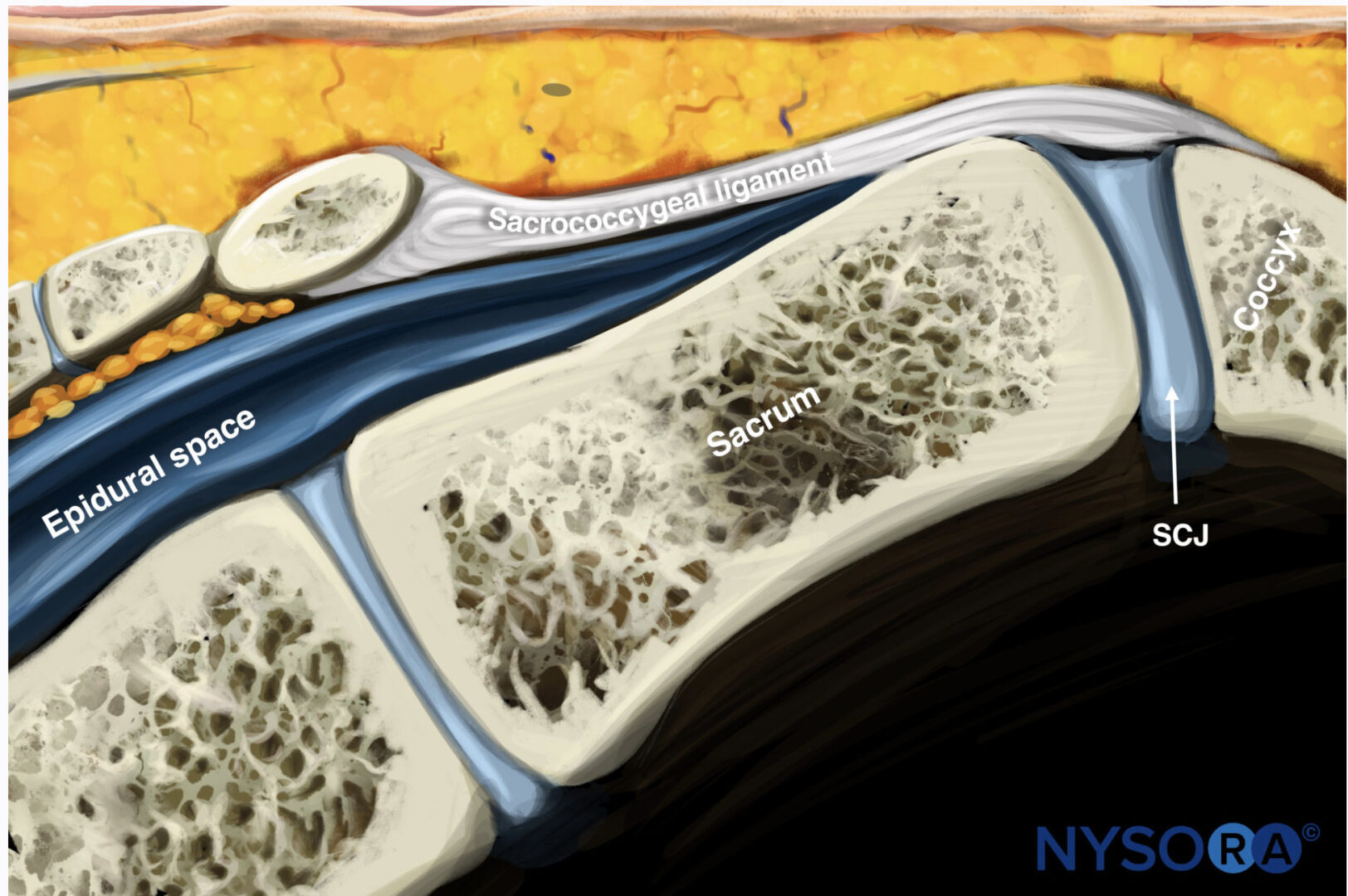

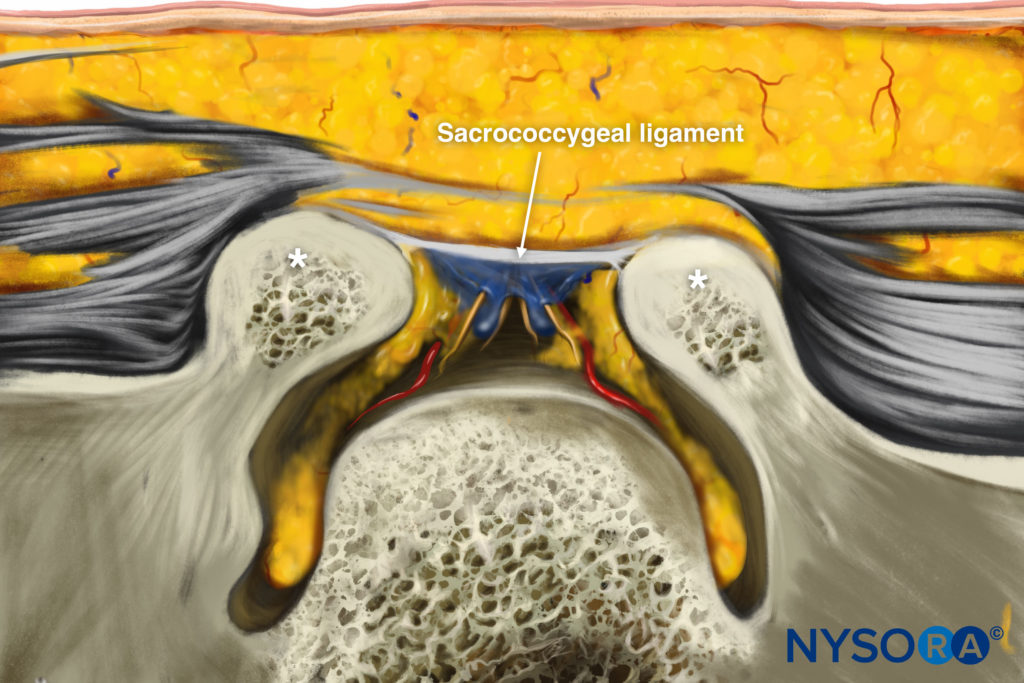

Anatomy The sacrum and coccyx are formed by the fusion of eight vertebrae (five sacral and three coccygeal). There is a natural defect resulting from incomplete fusion of the lower portion of S4 and the entire S5 in the posterior midline. This defect is termed the sacral hiatus and is covered by the sacrococcygeal ligament. The hiatus is bounded laterally by the sacral cornua, and the floor is composed of the posterior aspect of the sacrum [1, 2]. The epidural space extends from the base of the skull to the level of the sacral hiatus. It is the space confined between the dura mater and the ligamentum flavum and surrounds the dural sac. It is divided into anterior and posterior compartments and bounded anteriorly by the posterior longitudinal ligaments, laterally by the pedicles and neural foramina, and posteriorly by the ligamentum flavum. The epidural space contains the spinal nerve roots and the spinal artery that pass through the neural foramina and the epidural venous plexus. Below the level of S2, where the dura terminates, the epidural space continues as the caudal epidural space that can be accessed via the sacral hiatus that is covered by the sacrococcygeal membrane. The sacral epidural canal contains the sacral and coccygeal roots, spinal vessels, and the filum terminale. The epidural venous plexus is concentrated in the anterior space in the caudal epidural canal [1, 3, 4].

1. INDICATIONS FOR CAUDAL EPIDURAL INJECTION

Caudal injections are usually performed as a diagnostic or therapeutic intervention in various lumbosacral pain syndromes, especially in cases of spinal stenosis and postlaminectomy syndrome, when lumbar epidural access is more difficult or not desirable.

2. LIMITATIONS OF THE LANDMARK “BLIND” TECHNIQUE

Anatomic variations of the sacrum and the contents within the sacral canal pose a challenge during caudal epidural steroid injections. Variations in sacral anatomy have been reported to be as high as 10% [5] and have resulted in misplaced needles in 25.9% of caudal epidural injections performed by experienced physicians without fluoroscopic guidance [6].

Inadvertent intravascular injection has been reported to range from 2.5% to 9% [5–7], and negative needle aspiration for blood has been shown to be neither sensitive nor specific [7, 8]. Intravascular injection is also more likely to be used in elderly patients because the epidural venous plexus may continue inferior to the S4 segment in these patients [9]. This provides the rationale for the need to perform caudal epidural injections with real-time imaging guidance in order to maximize the outcome and minimize the complications [10].

3. LITERATURE REVIEW OF ULTRASOUND-GUIDED CAUDAL EPIDURAL INJECTIONS

Klocke and coworkers [11] first described the use of ultrasound imaging in performing caudal epidural steroid injections. They found it to be particularly useful in moderately obese patients or patients who are unable to lie in the prone position. Lower frequency transducers (2–5 MHz) in obese patients were required to achieve adequate penetration. Chen and colleagues [12] evaluated ultrasound guidance in performing caudal epidural steroid injections in 70 patients with lumbosacral neuritis. They used a high-frequency transducer (5–12 MHz) to identify the sacral hiatus. The needle position was then confirmed by contrast fluoroscopy. They had a 100% success rate in needle placement but observed that the needle tip was no longer visualized after the needle advanced into the sacral epidural space secondary to the bony artifacts. This eliminated the possibility of identifying a dural tear or intravascular placement other than needle aspiration. This led Yoon and associates [10] to evaluate the use of color Doppler ultrasonography for caudal injections in order to identify intravascular placement. They injected 5 mL of the injectate while observing the flow spectrum in color Doppler mode. They defined the injection as successful if unidirectional flow (observed as one dominant color) of the solution was observed with color Doppler through the epidural space, with no flows being observed in other directions (observed as multiple colors). The correct placement of the needle was then verified by contrast fluoroscopy. In three patients, including two with positive Doppler spectrums, the contrast dye was outside of the epidural space.

4. ULTRASOUND-GUIDED CAUDAL INJECTION IS BETTER THAN THE “BLIND” TECHNIQUE

A retrospective study of caudal injections in 83 pediatric patients comparing the accuracy of caudal needle placement with the “swoosh” test, two-dimensional transverse ultrasonographic evidence of turbulence within the caudal space, and color flow Doppler concluded that ultrasonography is superior to the swoosh test as an objective confirmatory technique during caudal block placement in children [13]. They found the presence of turbulence during injection within the caudal space to be the best single indicator of block success.

5. ULTRASOUND-GUIDED CAUDAL INJECTION IS AS EFFECTIVE AS THE FLUOROSCOPY-GUIDED TECHNIQUE

Akkaya and coworkers [14] compared the results of ultrasound- and fluoroscopy-guided caudal epidural steroid injections in 30 postlaminectomy patients who were randomly divided into two groups. They concluded that caudal epidural steroid injection is an effective analgesic method for postlaminectomy patients and that the ultrasound-guided caudal block can be as effective as the fluoroscopy-guided block and even more comfortable.

Park and associates [15] compared the short-term effects and advantages of ultrasound-guided caudal epidural steroid injections with fluoroscopy-guided epidural steroid injections for unilateral radicular pain in the lower lumbar spine. A total of 120 patients with unilateral radicular pain were randomly assigned to either the fluoroscopy or the ultrasound group. This study showed that the ultrasound approach with color Doppler mode may avoid intravascular injectioninduced complications. The results showed similar improvements in short-term pain relief, function, and patient satisfaction with both ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance. Hasra and associates [16] compared ultrasound and fluoroscopy-guided caudal epidural injection techniques for both the time needed for correct needle placement and the observed clinical effectiveness. A total of 50 patients with chronic low back pain and radiculopahy not responding to conventional management were randomly assigned to ultrasound or fluoroscopy-guided caudal epidural injection groups. Pre-procedural Visual analogue scale (VAS) and Oswestry disability index (ODI) were noted. Time to correct needle placement was documented as well as any observed adverse events. Patients were followed for 2 months and VAS and ODI measured at regular intervals. The results showed that there was less time to correct needle placement with the ultrasound-guided technique and all observations of clinical effectiveness were comparable.

6. ULTRASOUND-GUIDED TECHNIQUE FOR CAUDAL EPIDURAL INJECTION

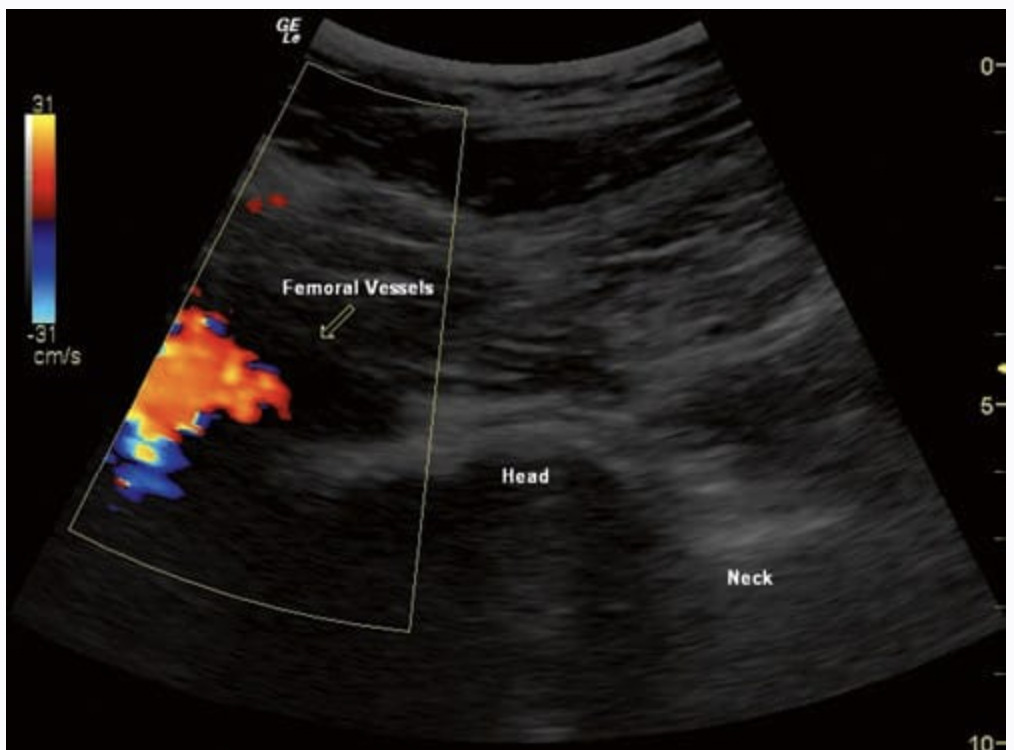

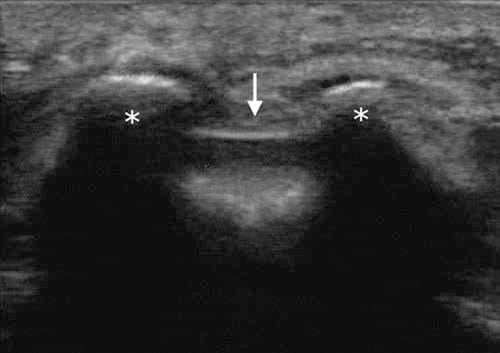

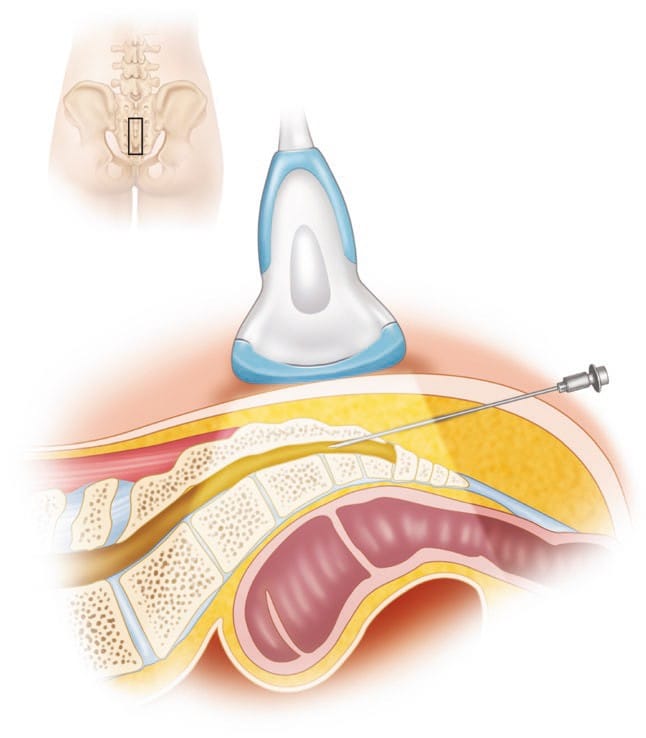

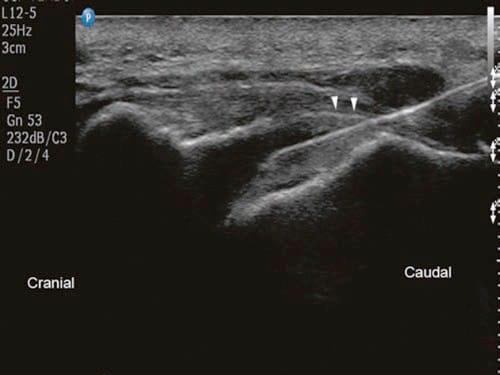

With the patient in the prone position, the sacral hiatus is palpated, and a linear high-frequency transducer (or curved low frequency transducer in obese patients) is placed transversely in the midline to obtain a transverse view of the sacral hiatus [12]. The bony prominences of the two sacral cornua appear as two hyperechoic reversed U-shaped structures. Between the two cornua, two hyperechoic band-like structures — the sacrococcygeal ligament superiorly and the dorsal bony surface of the sacrum inferiorly — can be identified, and the sacral hiatus is the hypoechoic area in between (Fig.1). A 22-gauge needle is then inserted between the two cornua into the sacral hiatus. A “pop” or “give” is usually felt when the sacrococcygeal ligament is penetrated. The transducer is then rotated 90 degrees to obtain a longitudinal view of the sacrum and sacral hiatus, and the needle is advanced into the sacral canal under real-time sonographic guidance (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig.1 Short-axis sonogram showing the two sacral cornua (asterisk) as two hyperechoic reversed U-shaped structures. Arrows indicate the sacrococcygeal ligament covering the sacral hiatus

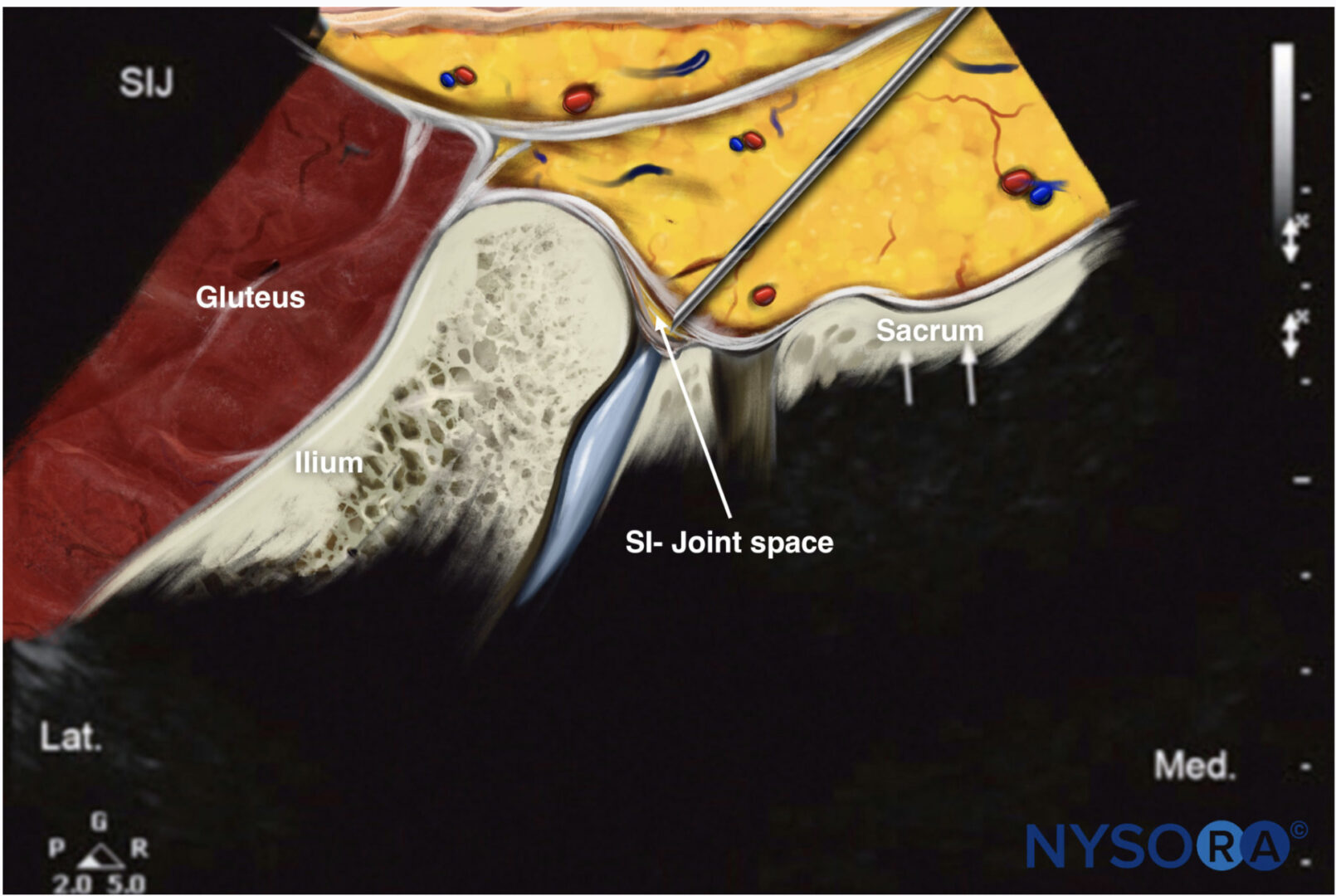

Reverse Ultrasound Anatomy illustration of figure 1.

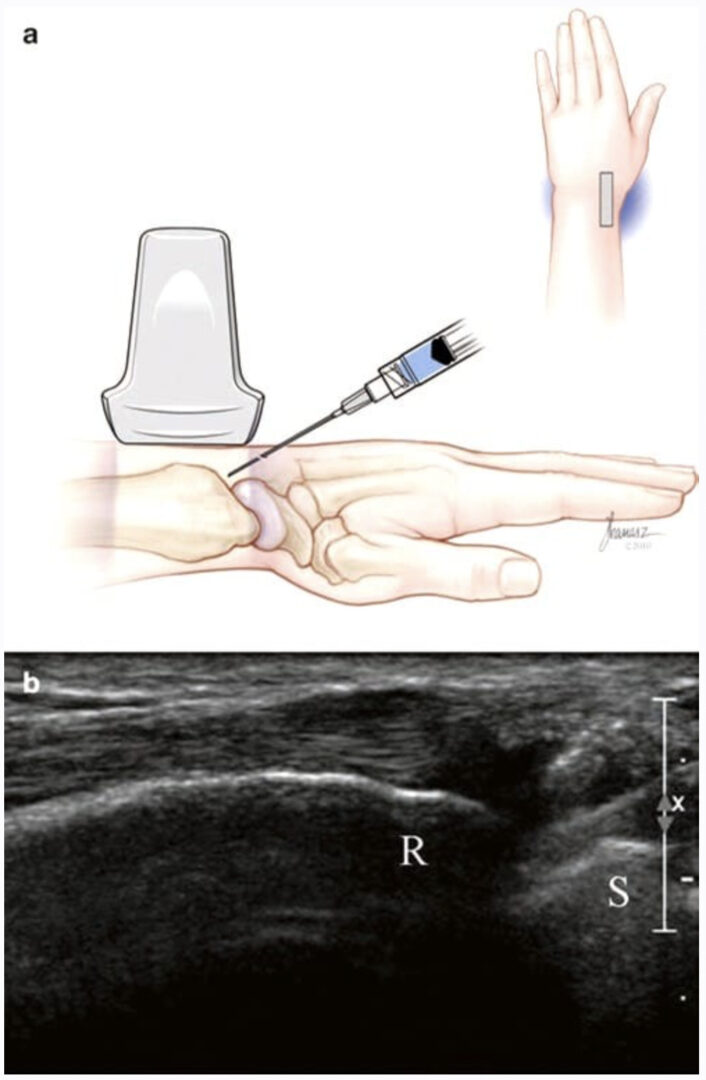

Fig. 2 The placement of the ultrasound probe over the sacral hiatus to obtain a longitudinal scan is shown

Fig.3 Long-axis sonogram showing the needle (in-plane) inside the caudal epidural space. Arrowheads point at the sacrococcygeal ligament. (Reprinted with permission from Samer Narouze, MD, PhD (Ohio Institute of Pain and Headache))

7. LIMITATIONS OF THE ULTRASOUND-GUIDED TECHNIQUE

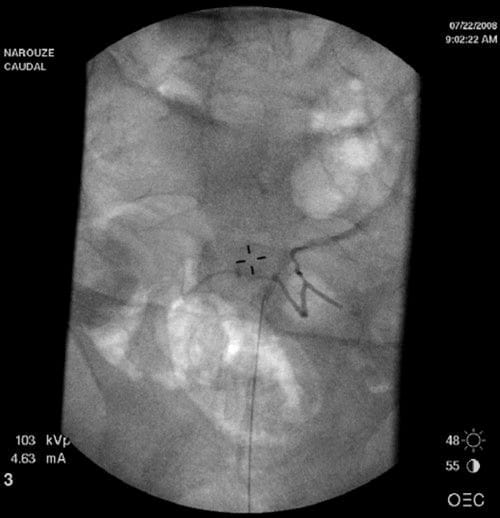

In adults, it is usually difficult to follow the needle inside the sacral canal secondary to the bony artifacts from the sacrum, and accordingly a dural puncture or intravascular placement cannot be readily identified. Since negative aspiration is not reliable, we recommend a test dose injection first to rule out intravascular or intrathecal placement. The injection is carried out under real-time sonographic guidance with monitoring of the turbulence in the sacral canal and the spread of the injectate cephalad. Color Doppler mode may be used to facilitate this, as discussed earlier [10], but it is very unreliable because turbulence from the injectate can be interpreted as flow in many directions and can be misinterpreted as an intravascular injection. Contrast fluoroscopy remains the best tool to evaluate inadvertent intravascular needle placement in this area (Fig. 4). Ultrasound can be used if fluoroscopy is unavailable or contraindicated or as an adjunct to guide needle placement into the sacral canal in difficult patients.

Fig.4 Anteroposterior radiograph showing intravascular spread of the contrast agent during caudal epidural injection. (Reprinted with per-mission from Ohio Pain and Headache Institute)