Learning objectives

- Describe common causes of VAE and high-risk procedures

- Prevent VAE

- Manage VAE

Definition and mechanisms

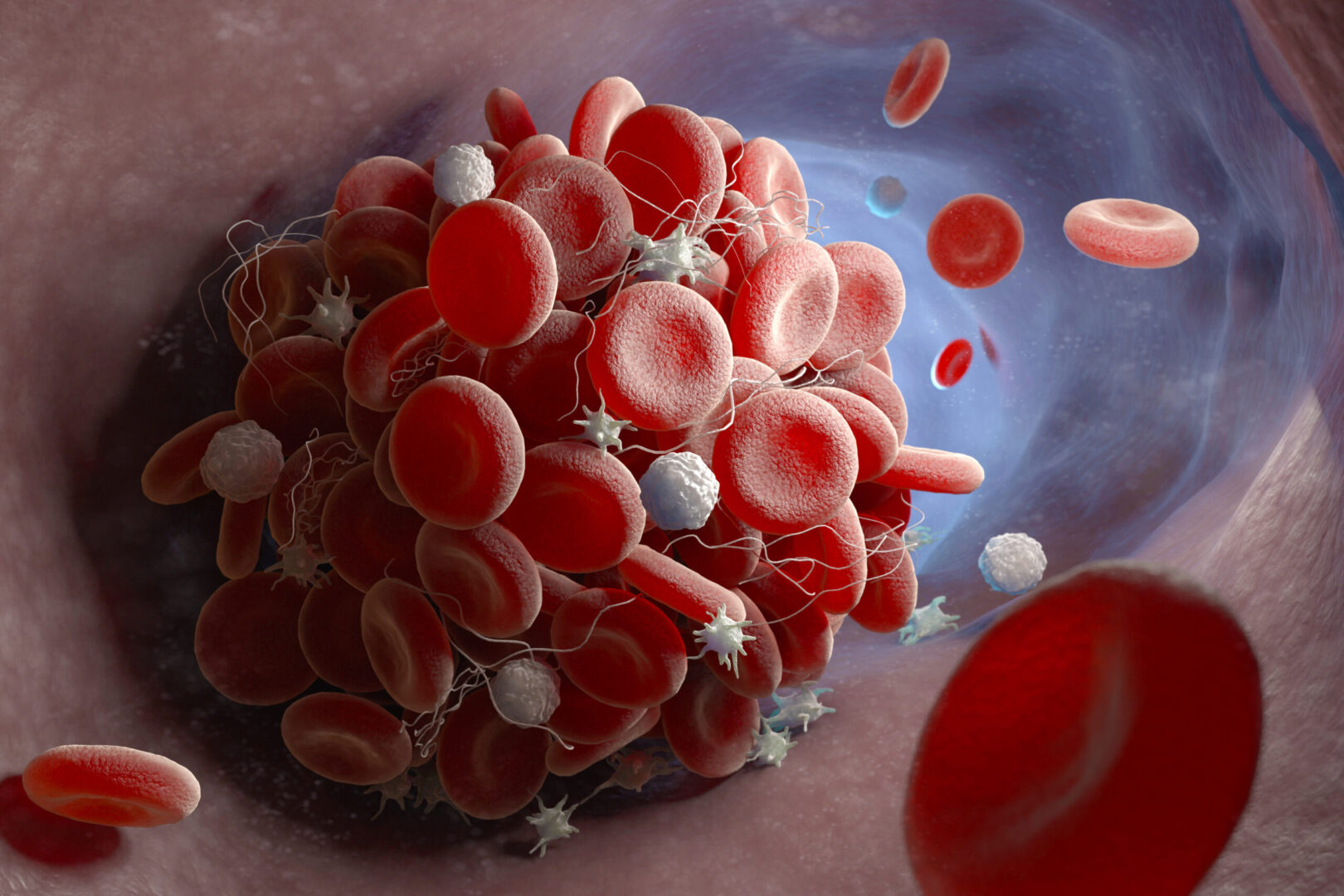

- Venous air embolism (VAE) is caused by the ingress of gas into the venous system, most commonly air

- Rare iatrogenic complication in a wide range of clinical scenarios involving line placement, trauma, barotrauma, and several types of surgical procedures including cardiac, vascular, and neurosurgery

- Traditionally, surgery and trauma were the most significant causes of air embolism; now, endoscopy, angiography, tissue biopsy, thoracocentesis, hemodialysis, and central/peripheral venous access comprise a greater proportion

- May cause end-organ ischemia or infarction.

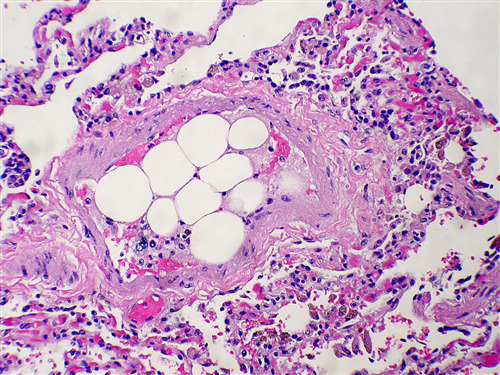

- May cause direct endothelial injury leading to the release of inflammatory mediators, activation of the complement cascade, and in situ thrombus formation

Signs & symptoms

- The presentation of VAE is dependent on the rate and volume of air entrained; Signs include:

- Apnea

- Hypoxia

- Cardiopulmonary collapse

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Altered mental status

- Decreased conscious level

- Focal neurological deficits

- ‘Mill wheel’ murmur on cardiac auscultation

- Pulmonary edema may develop later

- Light-headedness, vertigo

- Breathing difficulties

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Sense of impending death

- ETCO2 falls

- Arterial oxygen saturation falls

- Hypoxemia

- ECG abnormalities (tachyarrhythmias, atrioventricular block, signs of right ventricular strain, ST-segment elevation or depression, non-specific T wave changes)

- Transesophageal echocardiography is the most reliable monitor to detect VAE

Prevention

- Patient positioning: avoid the sitting position and Trendelenburg position during the insertion of central venous catheters, try to prevent a negative gradient between the open site veins and the right atrium (increasing right atrial pressure via leg elevation and using the “flex” option on the operating table control)

- Holding ventilation when placing tunnel catheters

- Removal of temporary catheter synchronized with active exhalation/Valsalva maneuver or positive end-expiratory pressure

- Avoid nitrous oxide

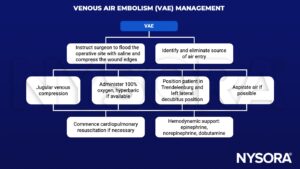

Management

Suggested reading

- Chuang DY, Sundararajan S, Sundararajan VA, Feldman DI, Xiong W. Accidental Air Embolism. Stroke. 2019;50(7):e183-e186.

- McCarthy CJ, Behravesh S, Naidu SG, Oklu R. Air Embolism: Diagnosis, Clinical Management and Outcomes. Diagnostics (Basel). 2017;7(1):5. Published 2017 Jan 17.

- Mirski MA, Lele AV, Fitzsimmons L, Toung TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of vascular air embolism. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(1):164-177.

- Webber S, Andrzejowski J, Francis G. Gas embolism in anaesthesia. BJA CEPD Reviews. 2002;2(2):53-7.

We would love to hear from you. If you should detect any errors, email us at customerservice@nysora.com